at the Museum of Modern Art, New York

September 2005-January 2006

By Michael Wells

Part 1

The fall of 2005 is shaping up to be a stunning

season for New York fans of Asian film, what with one festival after another

devoted to new Korean film, classic and hard-to-see Japanese film, classic

and hard-to-see Chinese film, and so on and on. The only problem

is deciding what you have the time and money to see. My membership

at the Museum of Modern Art makes one choice pretty easy. This series

runs until January of ’06 and includes fifty-three movies covering the

years 1929 through 1970, in new archival prints with new English subtitles.

Despite my tendency to lapse into shudders of pleasure that make typing

difficult, I’ll do my best to keep a running account of this great leap

forward in my Japanese cinema education. Check this space every once

in a while for the rest of the year to see more or less off-the-cuff comments

on my latest viewings.

The Emperor’s first film as a full-fledged director is, needless to say, remarkably confident and beautiful for a “novice.” Of course, you have to remember – as I was reminded when I dipped back into Kurosawa’s Something Like an Autobiography – that in those days, filmmakers served long, rigorous apprenticeships learning all aspects of their craft, rather than leaping straight from shooting music videos and TV spots into feature directing. (A process allegorized in the movie itself: Sanshiro is certainly an ancestor of countless martial arts movies about callow youth whipped into shape by training under wise, take-no-b.s. masters.) The realistic, low-key fight sequences could hardly contrast more sharply with the flights of fancy with which we’re familiar. But they’re graceful, humorous and enormously pleasurable all the same. To be sure, there are clumsy scenes and hesitations; in particular, the movie’s attitude towards the action movie ethic of honorable violence seems less ambiguous or evenhanded than confused and uncertain.

Early Autumn (aka End of Summer). 1961, Yasujiro Ozu.

Congratulate me... I just broke my Ozu cherry, and high time, too. Clearly I’ve been missing out. This is one of those movies during which I occasionally ask myself, “Why am I enjoying this so much? Nothing’s happening!” Ozu settles you so skillfully and comfortably into his warm, gentle, funny-sad portrait of family life that it would be easy to take this for, oh, the Japanese equivalent of a Norman Rockwell painting. But still waters run deep. I guess Ozu has a reputation these days as something of a conservative, who counsels submission to the whims of fate and social convention (which are often the same thing). On the basis of this one movie, I see a storyteller with a painfully clear-eyed, unbiased insight into the upheavals of social change and generational conflict. He is able to sympathize equally with the exasperated young who look at the older generation and wonder, “Will I never be out from under this thumb?”, and the elders who look back and wonder, “Will they never understand what I sacrificed for them?” He made me feel the gracious comforts of familial bonds and their strangling hold as well, for young and old. And he made it look easy. Greetings, Ozu-san. Nice to meet you. We’ll be seeing plenty more of each other.

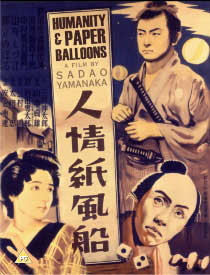

Humanity and Paper Balloons. 1937, Sadao Yamanaka.

According to some biographers, 29-year-old Yamanaka got sent to the front as cannon fodder by the wartime government as a direct result of this, his final film. At first glance, it’s tough to see from our vantage point what would so anger anyone in this compassionate and humanistic (if pessimistic) story of a poor neighborhood in the Tokyo of the Tokugawa Era (17th-19th centuries). But compassion and humanism were hardly the leading values of the country’s rulers at that time, and talking about poor people has long been a way to get yourself in trouble if you’re a liberal and your government isn’t. Plus, the fairly jaundiced (though quite humanized and nuanced) portrayal of the samurai class couldn’t have endeared Yamanaka to the military elite then in power. For a current American viewer, this view of samurai as ordinary people, firmly set in a social context of the other classes with which they interacted, is the most startling thing about the film. What holds the attention, though, is the vividly atmospheric recreation of the setting and the acutely convincing presentation of the people who lived in it. Especially finely balanced is the blend of solidarity and mutual irritation with which the residents regard each other as they live practically in each other’s laps, day in and day out.

Michael Wells can be contacted here.