A Centenary of Chinese Cinema

at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, New York

October 21-November 10, 2005

Screenings of the rarely screened are a dime a dozen in New York City, but even here, this was a clear-your-schedule and damn-the-budget event: more than thirty Mainland Chinese films covering every decade from the ‘20s through the current one, in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the first films made in China by the Chinese. (See the complete catalog online here . Selections of more recent vintage included some of the usual suspects from the “Fifth Generation.” Not that they aren’t welcome – I was particularly tempted to experience on the big screen the primal/pastoral images of Chen Kaige’s “Yellow Earth” (1985) and the bone-rattling power of Zhang Yimou’s “To Live” (1994). But I decided to concentrate on the stuff I can’t, and probably never will be able to, get on video here, the old classics. Even then, I inevitably and frustratingly had to miss a large number of those films I wanted to see – that’s the eternal paradox of abundance.

I was a little disappointed that the series didn’t feature any of the classic wuxia (martial arts swordplay) movies – little did I know that the Museum of Modern Art would soon compensate for this with their own Chinese series.

I should stop here and give some credit where credit is due: my enjoyment of the movies, as well as a lot of the background information I mention here, was greatly enhanced by my having read Jay Leyda’s 1972 book “Dianying/Electric Shadows: An Account of Films and the Film Audience in China.” This is a hefty history by an American author and film scholar who lived and worked in China for several years before fleeing the onrushing Cultural Revolution in the late ‘60s. As far as I know, there’s nothing to compare to it among works written in English for a Western readership (and anyone who knows better, feel free to e-mail me with recommendations). It’s a must-read for anyone seriously interested in the subject. The enormous amount of little-known-to-Westerners information, the rich texture of the times, the plentiful still images and other virtues more than make up for the often irritatingly condescending tone rather typical of a certain strain of scholar/critic of a certain generation (Hong Kong film fans will chafe particularly at his brief, dismissive handwaving at that industry and its popular products).

If there was one major lesson that sticks with me from Leyda, it’s that politics is inseperable from much, if not most, of Chinese film history (some would say that’s true for all film traditions – OK, it’s even more true here). The reasons ought to be obvious during the post-1949 Communist era. But the preceding “Golden Age of Shanghai Cinema” emerged during a civilization-shaking era of sociopolitical transformation and civil war. Leyda describes the film industry of that time as a tug-of-war between leftist and rightist studios and artists, often allied to particular political parties or movements. Their films succeeded at pleasing the mass audience while advocating, often explicitly, for their agendas, and watching a few examples, I felt a remarkable contrast with the Hollywood movies of the same era and their severe allergy to politics or controversy. The ages-old Chinese tradition of the storyteller’s and artist’s duty to educate and morally edify the audience may play a part; it would be fascinating to see a (far) more knowledgable person than I research that further and draw some more connections.

My favorite example might have been Zhao Ming and Yan Gong’s “The Peregrinations of Three Hairs” (1949), adapted from a popular newspaper comic strip about an orphan kid eking out an existence on the Shanghai streets, a phenomenon that was apparently epidemic at the time. It’s surprising enough that Zhao and Yan succeed at making a very entertaining, slapstick-heavy comedy on this subject (aside from the creepy makeup intended to make the child lead look more like his comics model, with his Charlie Brown-ish head). But they also do it without sacrificing a deep and palpable anger and while delivering bitter potshots at the social status quo, especially the indifference of the bourgeoisie. Despite the defiant energy and indomitable sass of the little hero, the “happy” ending where he and his pals get word of a (the?) Communist victory feels jarring.

Now, Communists, it must not be forgotten, tend to have very particular ideas about what constitutes a sufficient indictment of the bourgeoisie. Chen Xihe and Ye Ming’s “Family” (1957) apparently wasn’t it, as it got its makers, as well as people who publicly praised it, in hot water. I’m not sure what status Ba Jin’s 1933 source novel enjoyed or didn’t among the powers that were, but the film was apparently condemned as a reactionary justification of the old-fashioned feudal values that China was supposed to be shedding after the “people’s revolution.” The mind boggles at the perverse thinking required to interpret “Family” in this way. The film’s rage against oppressive tradition is scalding, even if it’s only unleashed in brief jets of steam, rather than a boiling torrent.

While the cast of characters is large, the story centers around the three grown sons of a well-to-do, respectable clan, and their respective choices to uphold, appease or rebel against the strictures that come with their positions. The surface of the movie is a polished gem: elegant production design, gently gliding black and white camerawork and understated performances. This surface is like a cage barely containing the film’s sense of a desperate lashing-out against family tradition. “Family” commits the sin of nuance, allowing even its nominal “villains” humanity and regarding them with compassion; the characters may be sociopolitical symbols first and foremost, but they’re people as well. Such capitalist running dogs, these filmmakers.

No one should be surprised that “Family” was not the only film in the series about the tug of war between ages-old Confucian notions of duty and social position on the one hand, and modern individualism on the other. Far less vivid and accomplished, but still worthwhile, was “The Peach Girl,” a 1931 silent by Bu Wancang, in which a well-to-do rural youth and a spunky poor girl dally in defiance of his imperious mother. An interesting footnote: I had already seen this movie, but had forgotten it. At a screening during the Guggenheim Museum’s small series of early Chinese films sometime in the late ‘90s, I was so bored and inattentive that I quickly forgot the title and the story. I’m glad I did – I quite enjoyed it the second time around, despite realizing not fifteen minutes in that it was a rerun. Whether that speaks to some major maturation in my tastes or patience, or to my moodiness, is open to question.

Regardless, even the first time around, I remember being impressed by Ruan Lingyu in the title role. Ruan was the most legendary Chinese actress of the ‘30s – her untimely death by her own hand at the height of her career certainly has a lot to do with that, but her star never would have reached such heights if she hadn’t been as luminous a screen presence as she was. For some reason she gets called “the Chinese Garbo” quite a lot, but I can’t see much similarity. Ruan is marked by a very direct and human – I almost want to say “earthy” – presence despite her beauty and delicacy. She looks like she ought to be a shrinking violet, but she rarely comes across that way. Even when playing an oppressed victim, she possesses an inextinguishable spark of defiance and integrity. And she just knows how to act – her facial expressions flow as fluidly and naturally as a breeze over the surface of a pond, in a way that’s almost startling next to the more stylized performing typical of so many silents, especially Chinese ones. Ruan singlehandedly turns a decent, nobly intentioned melodrama into something engrossing. I notice that I’ve slipped into the present tense while discussing her. There you go.

Ruan gets less chance to shine in Bu’s “A Spray of Plum Blossoms” (1931), handling a supporting part in a goofy, blithely anachronistic adventure-comedy-romance, sort of a loose, modern-dress take on Shakespeare’s “Two Gentlemen of Verona,” weirdly infused with some Robin Hood-ish swashbuckling. I’ll admit I went hoping it would be some relative of a martial arts film; the little I got out of it consisted of some camp amusement and maybe some academic interest in the way it tries to hybridize jazz-age Western and old-fashioned Chinese influences into something passing for a hip mass entertainment.

As one might expect, this was not the only piece that I would damn with the faint praise, “of academic interest.” Zhang Shichuan’s “Cheng the Fruit Seller” (1922; aka “Labourer’s Love”) was unmissable simply for being the oldest surviving Chinese film. Thank the fates it’s a short – even at thirty minutes, this virtually charmless slapstick romantic comedy is an endurance test, with a male lead whose broad comic stylings make the pop-eyed, “whaaaa!”-emitting performers of ‘80s Hong Kong film look like Buster Keaton.

It was followed by the comparatively distinguished but still dry “A Pearl Necklace” (1925) by Li Zeyuan. This opens promisingly with a stunning, abstract tracking shot of a nighttime street scene, lights hanging in the darkness like stars, but this is apparently an accidental virtue. The exasperatingly fastidious, visually flat domestic melodrama expands and dilutes Guy de Maupassant’s famously cruel short story “The Necklace,” in which a middle class couple comes to ruin when the wife borrows a neighbor’s baubles for a party. That classic, cutting tale of acquisitive folly, social roleplaying and just plain bad luck becomes a finger wagging lesson on, as the titles explicitly tell us, the dangers that female vanity poses to decent men. I vaguely recall hearing that “Pearl Necklace” has some historical value for its portrayal of contemporary, Westernized, middle-class urban life, but that didn’t do much at the time to soothe my sore butt.

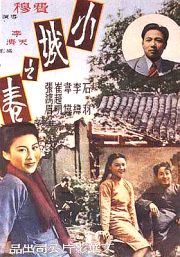

Maybe the film I most anticipated seeing was Fei Mu’s “Spring in a Small Town” (1948), which, it’s my impression, holds a position in China’s cinema roughly akin to that of “Citizen Kane” in America’s. I may as well be honest right up front: I made the mistake of going with insufficient sleep, and after a long day at work, and, yes, I dozed through a good portion of it. Feel free to throw tomatoes; I deserve it. Especially since I’m going to review it anyway.

“Spring” is a formally audacious psychological drama set in the rundown rural estate of a once prosperous family, where a thwarted romantic triangle develops among an unhappy wife, an ailing husband and her long-lost ex-lover who shows up for a visit. What I saw was lovely despite not being of a nature to keep one wide awake. Facile comparisons to familiar work is a bad critical habit, but I already did it in the last paragraph, so I’ll observe that Fei’s film feels like a black and white ancestor to the Wong Kar-wai of “Days of Being Wild” and “In the Mood for Love.” It’s all here: the powerful mood of melancholy and nostalgic regret, the voiceover ruminations from different characters, the theme of passion repressed and misdirected, the expressionistically lit and composed images in claustrophobic interiors that make bourgeois anomie look really, really attractive (surprise: it became a favorite whipping boy during the Communist era that began shortly thereafter).

I don’t think it’s just the common elements with Wong that make “Spring” feel remarkably unlike anything else from its era that I’ve seen from any country. It’s ahead of its time in some ways, but reverts to silent cinema quite often. For obvious reasons, this is the first Chinese classic I’d pick if some enterprising American distributor decided to put out a few of these movies on DVD. For the time being, if I want to get some idea of what I missed when my lids got too heavy, I might have to rent Tian Zhuangzhuang’s surprisingly acclaimed 2002 remake, which also played at the Lincoln Center series.

The hybrid of silent and sound was even more striking and nicely balanced in my personal favorite from the series. Yuan Muzhi’s “Street Angels” (1937) is a sentimental tragicomedy about a poor young Shanghai street musician torn between two sisters, one of whom is trying to avoid a life of prostitution and the other trying to escape from it. Confusingly, it’s supposedly a loose remake of American director Frank Borzage’s 1927 silent classic “Seventh Heaven” (which I haven’t seen yet) and not Borzage’s 1928 “Street Angel” (which I adore). Yuan took more than just plot elements: the tonal blend of the earthy and the ethereal feels very Borzage as well. It also reminded me of “Three Hairs” in fashioning sparkling entertainment out of material that would normally be cinematic lima beans – the inescapable inertia of slum life – without blithely dishonoring the gravity of the subject. I suppose that for a Chinese filmmaker, it helps that the audience has retained a strong taste for tearjerking tragedy that seems to have been largely lost in America, where “crowdpleasing,” even by 1937, had long since come to be synonymous with “upbeat.” Yuan’s talkie scenes are interrupted by silent pantomine passages and sing-along song interludes which are charming, touching and integrated into the whole with remarkable smoothness. The whole effect was to project that quality that keeps me, at least, coming back to Asian cinema: the paradoxical sensation of something at once familiar and from another world entirely.

Michael Wells can be contacted here.