By Michael Wells

Sometime a few years ago, I can’t even remember when now, the Japan Society in Manhattan hosted a nifty, little film series they titled “Japan Noir.” Following are patched-together comments on the films, from jottings made at the time. The Society is hardly alone in abusing the overused term film noir. Few of the movies really fit under that heading, and the “Noir” label belies the impressive breadth of approaches to the crime genre on display here. The following seven movies nicely illustrate the variety and depth that can be found within the conventions of “pop” or “genre” filmmaking.

All that said, who knows what label to slap on

Branded

to Kill? It’s a Seijun Suzuki film – that’s it. This 1967

work is the apex of the director’s legend: the B-movie maverick who surreally

subverted his routine studio assignments, making radical, postmodern pop

art masterpieces. That rep is more than a bit of a stretch, but Branded

is certainly divertingly odd. The incomprehensible story is only

part of its strangeness. Labyrinthine plots are pretty standard anyway

in the yakuza (“gangster”) genre, which has traditionally focused

less on action than on the rituals and politics of the underworld.

Even so, it seems at times as if Suzuki has simply ripped out fistfuls

of pages from the script about the ousting of Killer #3 (the top ten are

ranked) and his efforts to stay alive, regain his rank and get the girl.

That’s as near as I can figure it, anyway. But the tale dissolves

constantly into tomfoolery like the cosy standoff between #3 and an enemy,

as they hang out for days on end in his apartment, handcuffed to each other.

Or #3’s love scene with a gorgeous assassin on a bed of dead butterflies.

Or his vaguely sexual obsession with the aroma of boiling rice. At

any rate, Suzuki clearly has remarkable visual gifts: the glowing monochrome

images and ghostly tracking shots make that clear. But the film comes

across like a lark by a talented smartass. I’m not sure how much

I would have enjoyed it had I not known the backstory, which eventually

sees Suzuki fired by his Nikkatsu Studio bosses. Half the fun is

imagining the suits gaping in exasperation while the prodigal hack giggles

in the back of the screening room.

When it comes to subverting the yakuza film with a unique sensibility, no one today surpasses Takeshi Kitano. The protagonist (“hero” would be a stretch) of Boiling Point (’90) is a dimly apathetic, sleepy-eyed gas station attendant. When he finally musters a little personal initiative, he does so in typically clueless fashion, taking a swing at a rude local mob member. Of course a chain reaction of explosive retribution ensues, but since this is Kitano, the fuse burns in slow motion and keeps heading off in unexpected deviations, fizzling out only to pick up somewhere you’re not looking. Kitano is the Renaissance Man of contemporary Japanese pop culture: a stand-up comic, a movie star, a TV host with something like five or six weekly primetime shows, a columnist and bestselling author, and internationally acclaimed director (Sonatine, Fireworks). In addition to directing and writing, Kitano, as usual, bruises up the screen under his acting name of Beat Takeshi, bringing an even meaner streak than usual to his customary role, the poker-faced but pugnacious hard case. Boiling Point is where the filmmaker pretty much perfected a patented blend of the comical, vicious and melancholy. His deadpan, long-take filmmaking has rarely been funnier or more mesmerizing, the dry-as-toast style rendering absurd all the posturing and pummeling. There was hardly a scene in which I didn’t laugh like a hyena… yet somehow I was always aware of a steely edge of menace, like a straight razor lightly touching the back of my neck.

Compared to works like these, Yoshitaro Nomura’s The Chase (’57) feels grandfatherly in its classical restraint. It patiently observes two police detectives as they patiently observe a young housewife and await the possible arrival of her ex-lover, a murder suspect on the lam. (“She spent eighty yen on fish and vegetables,” is about as hard-boiled as their cop talk gets.) The first half, with the men holed up in an inn across the road, is marvelous – it builds a lovely sense of place in a small-town, postwar Japan that I imagine being a thing of the past now. Only three years after the release of Rear Window, we have again the claustrophobic waiting and peeping-tom surveillance amid a sticky summer heat wave, full of the sounds of a bustling community that is all open doors and windows. While the story stays there, the title seems intended ironically – then, once the actual chasing begins, Chase paradoxically becomes less exciting. It retains its refreshing humanist approach to the end, though, and its observant sympathy for all the characters: the quarry, though he is likely a killer, the detectives, though their mission arguably comes to seem of dubious value, and especially the young woman caught in the middle. It’s one of those movies that makes me wish the source material – in this case, a novel by renowned and prolific crime author Seicho Matsumoto – were available for reading in English.

Shohei Imamura’s tense and extremely funny Endless Desire (’58) is also about crime and endless waiting in a small town. But this village setting is no center of nostalgic values. Mostly, it’s an unending font of annoying obstacles for the antiheroes, a handful of crooked war buddies and a shady femme fatale meeting after ten years to dig up a buried cache of black market morphine. The setup, the central characters, the ivory-and-ink look, all are pure film noir. But as they tunnel slowly beneath a bustling market street towards their secret stash, the effort dissolves into a dark comedy of errors thanks to their individual weaknesses (greed, impulsiveness, greed, lust, greed, stupidity, and greed) and the meddling of locals. Communal values come across as nosiness and small-town innocence as naivete, but of course the jaded vileness of the conspirators is hardly preferable. Unfazed, Imamura leavens the lip-smacking misanthropy with just a touch of his usual affection for all kinds of screwups and outcasts.

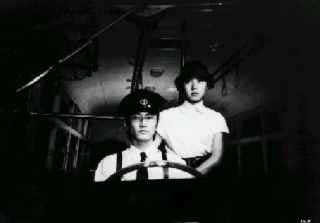

The woodsy back roads and narrow, sleepy streets of semi-rural Japan are used to another effect completely by Sogo Ishii in the hypnotic Labyrinth of Dreams (’97). Intriguing sociological details of old-fashioned life (the polite care of bus conductors is wondrously quaint to this 21st century subway rider) float about like dandelion seeds in the movie’s sleepwalking drift. Ishii puts the audience thoroughly inside the parallel mental universe of the heroine, a lonely conductor who suspects that a handsome new driver is the rumored killer given to seducing colleagues and then murdering them in staged accidents. Exhausted at the end of a long week, I was in just the right state to follow her and her director down the rabbit hole. I sat in a trance-like daze (similar to that affecting the actors?), washed by the black and white cinematography that was somehow both stark and glowing. The Japan Society’s program claims that Labyrinth “depicts the intricate psychology” of the female lead, but it seems to me that the poor girl’s head problems are pretty straightforward. Ishii is interested more in the enveloping atmosphere than in character study or even suspense – though there’s a healthy amount of that before the end.

These days, any retrospective in this genre would have to include a piece by Kiyoshi “no, I’m not related to Akira, dammit” Kurosawa, the current critical darling of Japan’s resurgent cinema and an artist who has returned regularly to crime and the macabre. The Society, though, made a nice choice to reach back into his days of B-movie and straight-to-video obscurity for The Guard from Underground (’92). There’s little of the now-typical Kurosawa of eerie abstraction. Guard is full-blooded black comedy/horror about a young woman whose new job perks include a hulking security guard given to obsessing over her and bumping off her colleagues. The movie wrings as much anxiety out of 9-to-5 life as it does out of stalking monsters and particularly nails the terrors of adjusting to the personality quirks of new co-workers (nearly all of the “normal” men, no less than the villain, see the heroine as a blank screen for projecting their fantasies). The two tracks merge best in the marvelous third act, a funhouse of look-behind-you! suspense and nervous giggles. Kurosawa is already firmly in control of his typical visual strategy, wrapping the sets in elaborately lit swaths of light and darkness to direct the eye and shape the tension. Of course, the vision of the modern office environment turned into a killing ground is as much a fantasy as a nightmare: there’s something perversely satisfying about the demolished desks, battered-down doors and crumpled paperwork that litter the climax.

The film noir label probably applies most comfortably to A Night in Nude (’93) written and directed by Takashi Ishii, one of Japan’s veteran specialists in grisly genre films. It’s built on the outline of many a noir, with the average joe hero who only half-unwillingly gets in over his head with crooks and killers. Ishii even includes the standard suspension-of-disbelief speed bump wherein our hero is required to behave like a moron in one scene to move the plot forward - appropriately, the character’s job description is “I do what needs doing.” Hired as a Tokyo tour guide by a femme fatale, he soon finds himself with a body on his hands, a web of deception around him and a growing collection of bruises and lacerations on his face. Ho-hum on paper, but Ishii takes the clammy-palmed sensation of a wrong turn down a dark street in a bad neighborhood and suffuses the whole movie with it, like some clinging slime. Better yet, he surprised me with his contagious compassion for the scarred and naked souls who inhabit this night, making Nude seem like it’s about something slightly more than its own florid nastiness.

Michael Wells can be contacted here.