After consolidating their power in the late 1960s by defeating MP&GI and striving to make films for the rising youth generation, Shaw Brothers met a new threat in 1970. Raymond Chow, a former production chief for Shaw Brothers, left the company to form his own called Golden Harvest. His biggest move in the industry was undoubtedly bringing Bruce Lee to Hong Kong and it was this arrival that marked the beginning of many problems for the Shaw organisation.

INDUSTRY

Golden Harvest formed as a response to the studio system of Shaw Brothers. Raymond Chow had reportedly left the company due to Run Run Shaw’s militaristic approach to running the studio (1) by how "he stressed not so much artistic innovation as standardization, rationalization, mechanization and efficiency" (Fu, 2000:79). Because of Shaw’s aggressive attack on MP&GI, Chow found luck in being able to buy the studio lot of Shaw Brothers former rivals. This posed a major problem for Shaw Brothers as a major company with MP&GI’s assets was once again challenging Shaw but this time the management was in Hong Kong so the ability to outpace production like they could with MP&GI was no longer feasible.

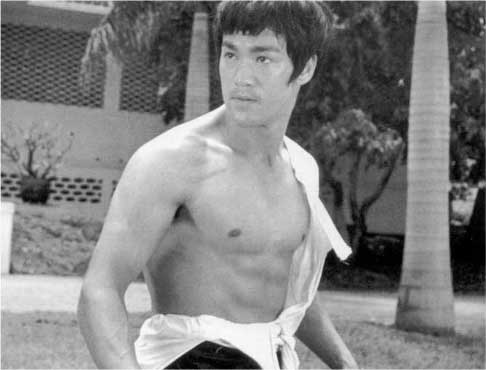

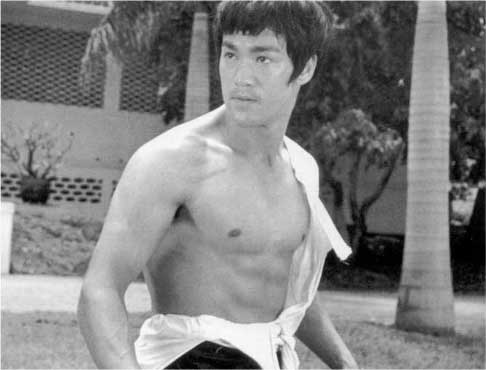

Golden Harvest’s mode of production was the opposite of Shaw Brothers. Instead of fixed contracts, Golden Harvest decentralised production, working through a system of independent organisations that "contrary to Shaw Brothers' emphasis on huge scale and absolute control, which was typical of the studio system, Golden Harvest preferred "an independent production system where stars and directors could agree mutually profitable deals with the studio" (Zhang, 2004:179). For example, Golden Harvest would maintain “satellite” companies such as Concord Productions where Bruce Lee had broken records with his breakthrough film The Big Boss (Lo:1971), this arrangement put Lee on an equal footing with Raymond Chow, as opposed to simply being a hired actor. The result undermined Shaw Brothers’ studio system where actors began to realise that fixed contracts were potentially fatal to their careers. Before Golden Harvest, Shaw Brothers had a virtual monopoly on the industry with no real threats to their dominance but with Golden Harvest supporting independent studios, stars knew they could make more money elsewhere.

It was this offer of creative control that tempted Bruce Lee to join Golden Harvest. Lee had originally approached Shaw Brothers with a demand of US$10,000 a title but Shaw only offered US$2,000 per film and a 7 film contract. Shaw Brothers, despite Lee‘s potential, had fixed rates for offering new actors contracts and Shaw was not going to change that stance. Golden Harvest on the other hand countered with an offer of US$7,500 per title (2). While less money than what Bruce Lee wanted from Shaw Brothers originally, it did mean that Lee would gain the creative control that he desired and commercial stakes in his enterprises. Creative freedom was something that Run Run Shaw was not likely to give to his actors (3) as mentioned in the first chapter, he systemised and centralised the studio so that his decision was always final on matters such as script approval.

Using the talent of Bruce Lee, Golden Harvest capitalised on his potential and garnered the highest revenues seen at the box office. Originally The One Armed Swordman was one of the most profitable films in Hong Kong making over HK$1 million, however Bruce Lee’s debut film; The Big Boss made HK$3.2 million (4) and its success "ultimately resulted in the rise of a quasi-independent production mode in which a big studio such as Golden Harvest made deals with big stars to produce mega-hits and share profits" (Teo, 2000:97). While Shaw Brothers at the time had better production values, Golden Harvest now had greater star power and the Shaw studio system showed its first signs of weakness.

AESTHETICS

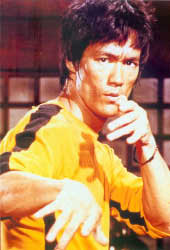

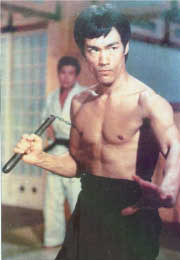

With creative control, Bruce Lee was able to escape the confines of formulaic production line films and form his own style. He was not only an actor but most importantly he was a highly skilled martial artist. Wuxia films had gone out of fashion with a further desire for realism and change from ancient Chinese tales, so kung fu had become the most popular genre of film in Hong Kong. Just as Shaw Brothers had continually recycled old stories for the huangmei diao genre, they fell into the same trap with the wuxia film, reusing old tales and themes and eventually it become monotonous. However what this genre did was pave the way for another type of martial arts film. Kung fu was seen as modern compared to the fantasy and myth associated with previous Chang Cheh period wuxia films. Bruce Lee was an instant sensation starting a kung fu trend featuring “real” fighters using their own strength to fight without the gadgets and flying accustomed to many titles featured in the wuxia genre.

Run Run Shaw was aware of the hype being created by Bruce Lee and so Shaw Brothers’ own kung fu film, The Chinese Boxer (Wang:1971) was released ahead of Lee’s film The Big Boss. This demonstrates the keen business sense and ingenuity of Run Run Shaw, by making Shaw Brothers the first company to release a kung fu movie, taking away the spotlight from Lee’s arrival. At the time of being released, this move had worked because the audiences were experiencing a new type of action movie. The Chinese Boxer had more gritty realism than even Chang Cheh’s films with the lead character played by Jimmy Wang Yu using his raw strength to rip peoples eyes out and snap necks. But it also exhibits evidence of a rushed project to pre-empt Lee’s arrival. The film sacrifices artistic innovation, recycling the tired revenge narrative along with the typical heroic bloodshed styled character archetype from the 60s featured previously in many Shaw films (5) (a result of production line methods) which was further weakened by the insufficient physical ability of it‘s star.

Jackie Chan notes that Bruce Lee was a different kind of martial arts fighter. He says that "the film [Big Boss] showed a different kind of hero and a harder, faster, and more exciting kind of martial arts fighting- as quick and lethal as a cobra strike, pared down to the bare essentials" (Chan, 1999: 165). This fighting style was new to the audience mainly because they had been accustomed to actors performing martial arts but not martial artists performing the moves. Jimmy Wang Yu for example was never formally trained in fighting and required the choreographer to break down the moves for him one step at a time and he would mimic the actions (6) (learning the skills when required). Whereas Bruce Lee had trained since a young age in a form of martial arts called Wing Chun (7), so the audience was seeing a real fighter executing moves and the difference was clearly noticeable. For instance in the climatic battle of The Chinese Boxer, the hero executes five separate kicks on the villain and for those kicks, the shots are broken down into five separate shots along with various flips and somersaults, making the fight theatrical rather than realistic and breaking the motions. This disrupts the action and fluidity, and places into question the natural talent of Jimmy Wang Yu. On the other hand, "Bruce Lee insisted on longer takes and more distant views to assure viewers that his feats were real" (Bordwell, 2000a:214). Instead of broken down shots, Bruce Lee would position the camera so that the audience could see his whole body and know that there was no stunt double, executing numerous kicks in quick succession. For instance in Fist of Fury (Lo:1972), Lee when battling enemies in a Japanese dojo, proceeds to kick eight or nine of his foes in one take without pausing or editing the action/film into smaller shots.

Unlike King Hu’s filmmaking which uses constructive editing to create illusion, the lack of cuts emphasises natural ability as you can see Bruce Lee’s entire body performing kicks and punches as Bordwell notes, "the future belonged to a style that made constructive editing ever more crisp, legible and expressive" (Bordwell, 2000a:135). While King Hu was more interested in camera movements and trickery, Bruce Lee emphasised choreography and this led to a new form of realistic aesthetic, far away from the “dance-like” Peking Opera traditions of Shaw Brothers early kung fu films and wuxia epics. Bruce Lee’s approach was that “you learn kung fu in order to win real fights” (Bordwell, 2000a:52) which emphasises the gap between Lee’s realistic fights with King Hu’s dance theatrics and Chang Cheh‘s “artificial” fighters. So while Fist of Fury does reuse the revenge motif as its central theme, the story is allowed to often take a backseat since the addition of Bruce Lee’s charisma and talent allowed it to become a showcase of new forms of inventive choreography and editing which updated the genre.

Through independence, actors and directors had the chance to be inventive and escape the confines of the studio system. As previously mentioned Shaw always had to be kept up to date with film developments in his company and so productions usually took place in Movietown where he could monitor everything and have absolute control (alongside being cheaper than moving his cameras on location). But a company like Golden Harvest allowed creative freedom so stars like Bruce Lee could make their films wherever they wanted. Way Of The Dragon (Lee:1972) for example was the first ever Hong Kong film to be shot in Europe and not only did it give the audience exciting new visuals with the sights of a foreign country (instead of stock footage and painted sets) but it also indicated that kung fu films were moving into modern settings.

REPRESENTATION

Hong Kong society was beginning to change. No longer was there violence on the streets and the economy was improving so martial arts heroes began to change too (8) however the city and its people were still fragile from the past turmoil. Governor MacLehose (9) had just come into power and was starting to make changes to society such as economic stability and social welfare yet the violence of recent years was a close memory and this was a time of uncertainty if the changes could actually work. The steady transition in Hong Kong society from chaos to prosperity allowed change in the hero where training and victory were new themes instead of sacrifice and suffering. Shaw Brothers biggest kung fu successes of the early 1970s were The Chinese Boxer and King Boxer (Jeong:1973), both set in feudal Chinese eras with the Manchurians and Japanese as the villains. What Bruce Lee achieved outside the studio system was the ability to easily set his film in modern times and create a modern hero that could be more significant for the audience. While the themes of the period martial arts film may relate to the current times, as Chang Cheh’s violence was representational to the post 1967 moods, in The Big Boss and Way of the Dragon this was a hero fighting in present day scenarios, so perhaps the audience could see the direct link. Teo suggests "the fact that Hu has stuck to period subjects almost always set in the Ming dynasty indicates that he is a director who relies on conventions of genre and myth. His affinity with ancient history is a sign of his alienation from the present" (Teo, 1997:88). Shaw films created mythical Chinese pasts while Bruce Lee represented modernity and his efforts helped begin to produce a modern Hong Kong identity moving away from the tradition of wuxia (which is typically seen as an ancient China tradition of storytelling) to create a sense of individuality and uniqueness. "Golden Harvest was less mechanised and China-centric....Golden Harvest's productions gained vitality and freedom as they shifted from the 'China dream' to 'Hong Kong sentiments" (Kei, 2003:43).

Lee’s characters were far from the self-suffering hero of Chang Cheh’s films like in The Boxer from Shantung (1972) or The Heroic Ones (1970). This was a regular man put into irregular situations and foreign lands (10) as Chan says; "Lee's hero wasn't a stoic noble soul, living his life in search of honourable revenge. He was a street brawler, a juvenile delinquent, sent away from home because of his love of fighting. In short he was a real guy" (Chan, 1999: 165). For instance the heroes of The Heroic Ones are princes and in The Chinese Boxer, the hero is a highly accomplished martial artist who learns near supernatural powers to defeat the enemies. While on the other hand in Bruce Lee’s Way of the Dragon, the hero is regarded as a “country bumpkin” by other characters. This is an everyday working class man who connected with the youth more than a wealthy prince could. "(Bruce Lee's) arrogant and narcissist manners appealed to the young generation....the kung fu of Bruce Lee are demonstrations of a perfect body" (Lau, 1999:32)

The characters that Lee played were developments on Chang Cheh’s characters. For instance in The Big Boss, Lee plays a youthful and arrogant character that challenges the patriarchy (a drug lord) and fights for the innocent (the working class). Bruce Lee’s characters fight for the everyday man rather than the larger cause such as the Manchurian invasions. In The Big Boss and The Way of the Dragon the only reason that he has to fight is to protect his working class family. This was no longer the Chang Cheh model of a hero that must suffer for living in troubled times but a hero that could deal with his problems and succeed reflective of the transition from suffering to prosperity that Hong Kong was developing into during the MacLehose Era. Bruce Lee stood for a modern day martyr of Chinese self-respect, an updated version of the heroic model from Chang Cheh films that attempted to destroy the effete leading man. Bruce Lee emphasises that his fighting is real, (often demonstrated through real life tournaments) and the audience "are aware that his kung fu skills are not the result of supernatural strength or special effects" (Teo, 1997:114). Since his skills are available through training and fitness (11), the audience can take pride that Lee injects self-confidence into the common man who can achieve anything and destroys the “Sick man of East Asia” (12) stereotype with his body (instead of King Hu‘s heroes with artificial agility by “the glimpse”). Shaw Brothers representation of the leading hero was behind the times and trailing the much more relevant hero figure of Bruce Lee and this along with the cracks formed in the studio system, put Shaw Brothers behind their rivals for the first time.

However tragedy came to the Hong Kong film industry with the passing of Bruce Lee. With Golden Harvest losing their star, this was an opportunity for Shaw Brothers to capitalise and once again find their dominance in the Hong Kong film industry; however another type of hero was about to arrive which once again would upset the balance…

ENDNOTES FOR CHAPTER 2

(1) Information about Raymond Chow from I Am Jackie Chan (Chan, 1999:165)

(2) Information about Bruce Lee deals from Chinese National Cinema (Zhang, 2004:178)

(3) Jimmy Wang Yu for example asked Shaw Brothers for changes in his contract and the right to direct but Shaw didn’t agree and when refused, he left for Golden Harvest where he would be guaranteed creative control. *Information on Jimmy Wang Yu from The Cinema of Hong Kong (Desser, 2000:101)

(4) Figures taken from Chinese National Cinema (Zhang, 2004:178)

(5) For example, Chang Cheh in 1971 made The New One Armed Swordsman, which was partly a remake and an attempt to make money off the popularity of his own film 4 years previously, The One Armed Swordsman featured similar themes of revenge and mass bloodshed as does The Chinese Boxer.

(6) Noted in Planet Hong Kong (Bordwell, 2000a:207), Wang Yu was a trained swimmer.

(7) Information on Bruce Lee from Kung Fu Cult Masters (Hunt, 2003:30)

(8) Sourced from The Shaw Screen (Lui, 2003:172) which discusses the improvement of Hong Kong citizens lives after the troubles of 1967.

(9) Information on Governor MacLehose from The Shaw Screen (Lui, 2003:172)

(10) Bruce Lee sets himself out as “Chinese” against foreign oppressors. The Way of the Dragon features opponents highlighted as being from Japan, Rome and America and they are all defeated by Lee’s natural speed and strength. His characters are specifically Chinese and "Bruce Lee stood for...Chinese nationalism as a way of feeling pride in one's identity" (Teo, 1997:110)

(11) This is especially demonstrated in the warm up scene before the final fight in The Way of the Dragon where for a long period of time, Lee warms up and physically stretches showing off his body that emphasises to the audience that his skills are a result of his training.

(12) Chinese in cinema had often been given the

image of weakness, especially after Japan’s occupation in World War 2 and

in Fist of Fury this is emphasised in two scenes. One where

the Japanese villains call the Chinese, the “Sick Men of East Asia” and

the second where Lee’s character tries to visit a park but a guard stops

him, pointing to a sign saying “No Dogs and Chinese” humiliating his nationality.

But Lee’s character uses his strength to physically destroy both signs

and overcomes this prejudice and in doing so becomes a strong representation

for China and Hong Kong in particular. Instead of battling the Manchu’s

of Wuxia films, Lee was bringing an updated battle to contemporary audiences.