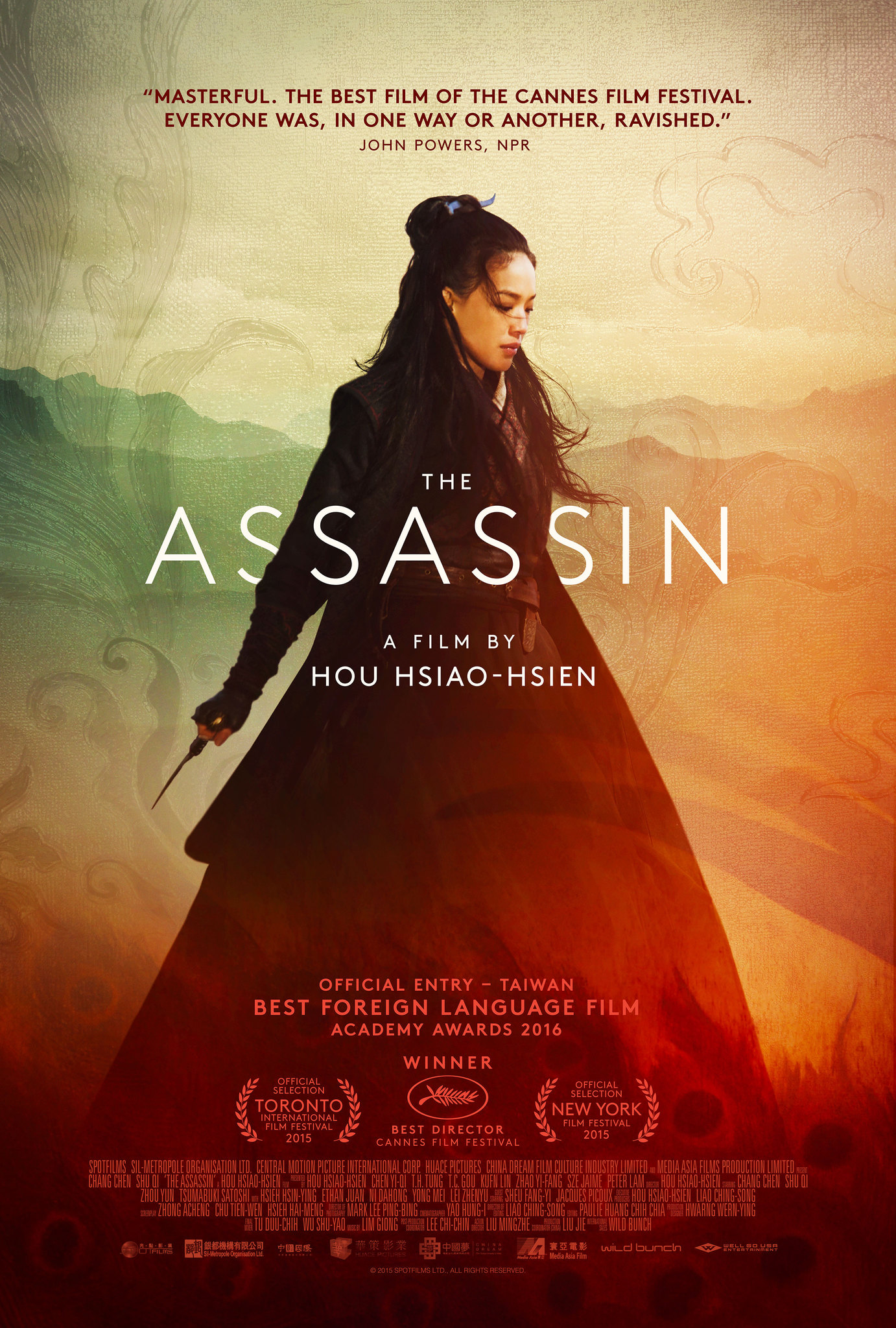

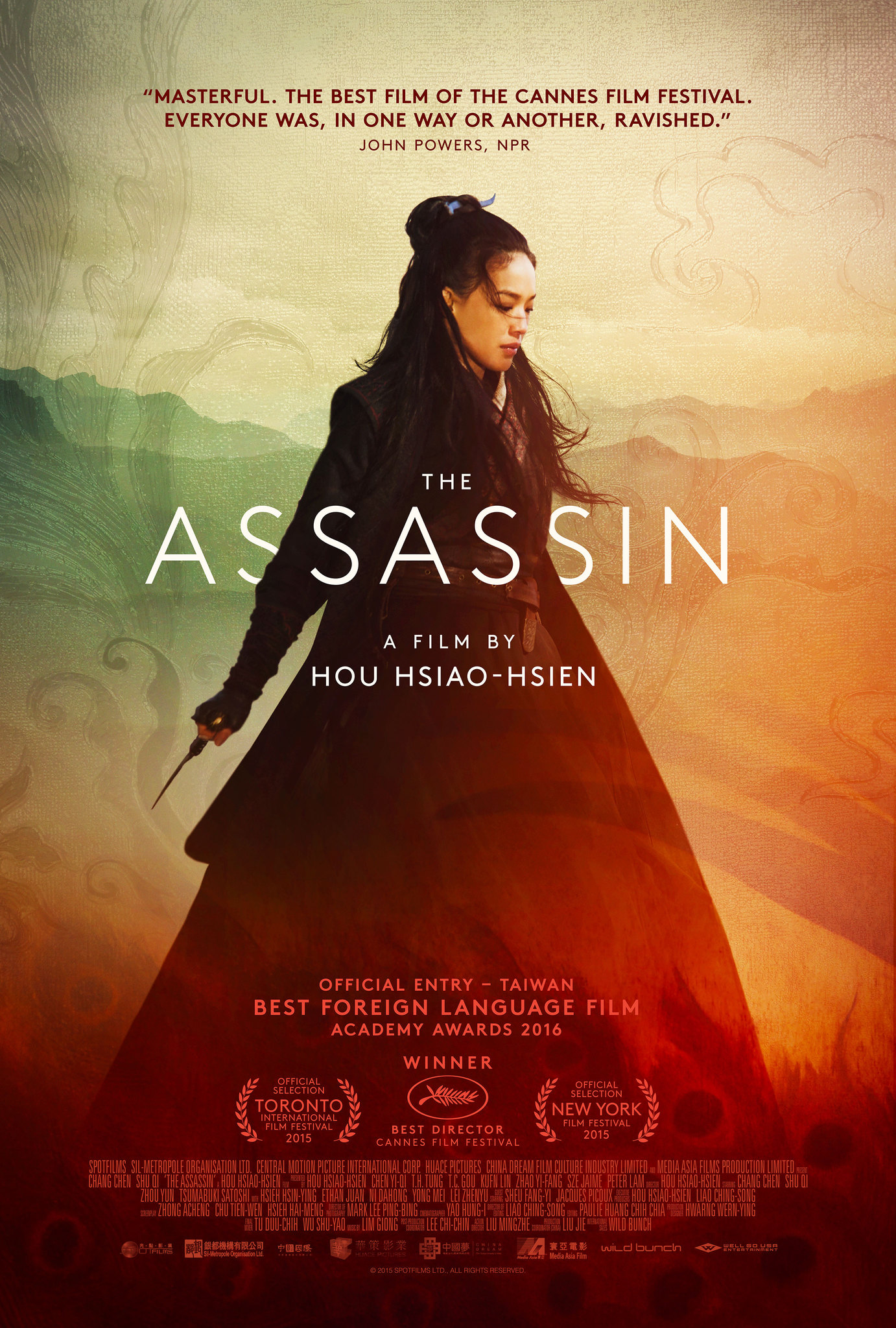

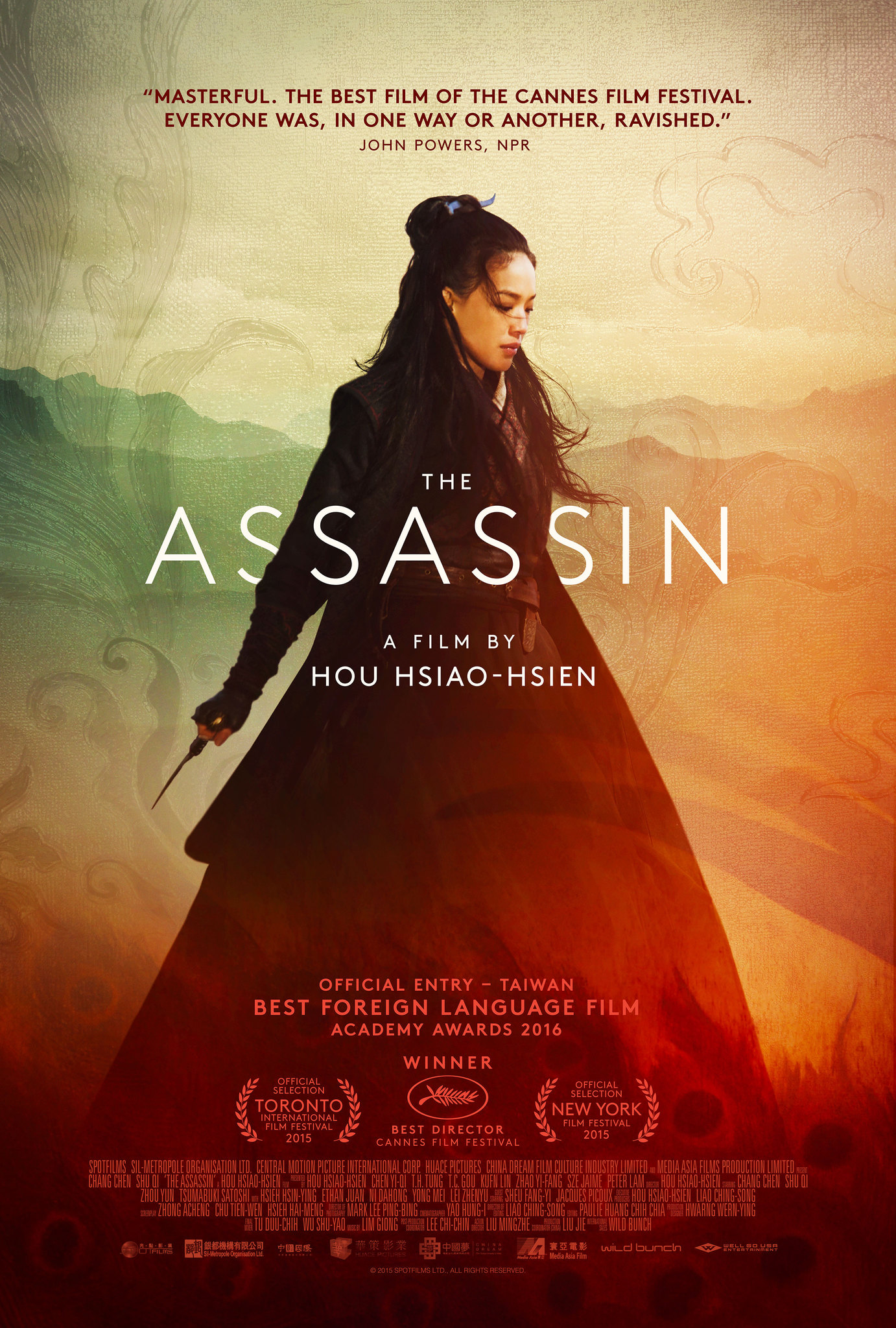

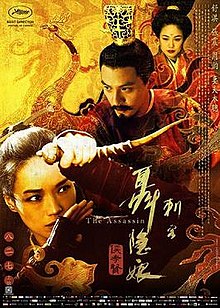

The Assassin

Director: Hou Hsiao-hsien

Year: 2015

Rating: 8.0

After his success

with dramas such as Ice Storm and Sense and Sensibility director Ang Lee

was asked why he wanted to make a Wuxia (Chinese heroic swordfighting) film

with Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and his response was something to the

effect that every Chinese director secretly wanted to make a wuxia. These

were the films and books that they had grown up on, they were the films that

spoke to the Chinese spirit and imagination. The films of King Hu, of the

Shaw Brothers, of Tsui Hark were part of their DNA. This turned out to be

true as we saw other well-known Chinese directors such as Zhang Yimou who

had previously directed classics such as Raise the Red Lantern and Red Sorghum

turn his hand to wuxia with the astonishing Hero and House of Flying Daggers,

Feng Xiaogang directed the stunning The Banquet and Chen Kaige (Farewell

My Concubine, Temptress Moon) made The Promise in 2005.

But even more surprising than those directors

taking up the tradition of wuxia films was when Hou Hsiao-hsien announced

a few years back that he too was going to make a wuxia. Hou Hsiao-hsien has

been one of the leading figures of the Taiwanese New Wave and his films –

The Puppetmaster, A City of Sadness, Millennium Mambo, Three Times, Flowers

of Shanghai among others – are thoughtful, artistic, static, at times impenetrable

and generally move as quickly as our ambitions on a hot lazy sunny day. He

has won all sorts of International Awards for the types of films that critics

usually love but that the masses stay away from like a dental check-up. People

were flabbergasted that he was going to make a wuxia film but lo and behold

it won him an award at Cannes.

It is a remarkable film in what it is and

what it isn’t. It fuses wuxia with strong art sensibilities and a heaping

of Shakespearean royal conspiracies and complexities. The plot is more than

a little elliptical and confusing to follow. It takes place in ancient China

and the small kingdom of Weibo is trying to hold on to its independence from

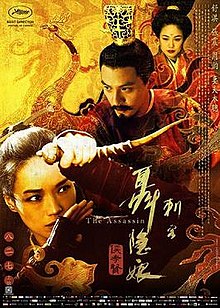

Greater China. Female assassin Yinniang (Shu Qi) is sent to Weibo to kill

its King Tian (Chang Chen – he was in CTHD) but her task is made harder by

the fact that she was once betrothed to Tian before she was sent away to

be trained as a killer. She takes on the persona of Hamlet as she walks the

ramparts and hills in chic black like a spirit wrestling with the decision

to kill him or not.

The film moves at the speed of a black

hole, but does so in as beautiful a manner as imaginable. The cinematography,

landscapes and detailed period sets are so exquisite and eye busting that

you want to bathe in them. HHH just lets scenes linger languorously for the

simple beauty of it. At times you feel like you are watching an art show

in slow-mo photos, each one selected with an eye for perfection. Beautiful

to watch even if slow and confusing but with an ending that is as quietly

humane as was that of King Hu’s A Touch of Zen.

Now for those who come to a wuxia with

expectations of great action scenes and beautiful movement, leave those expectations

at the door. There is very little fighting and when there is it is surprisingly

brief and often the camera even wanders away from it to touch on something

more human that is taking place off screen. Perhaps HHH felt that there was

nothing that he could do in that respect that would in any way say something

new or perhaps the ambivalent fighting scenes reflected the inner conflicts

of the characters. In most respects this is still an art film that just happens

to be a wuxia.

For those that may not be familiar with

the actress who plays the enigmatic reluctant assassin almost wordlessly,

she is Shu Qi, who in some ways has been the It Girl of Chinese films for

two decades. This Taiwanese actress first exploded on the scene in Hong Kong

in the mid-90’s with a series of erotic films that made good use of her naked

body. To some she was an untalented woman cashing in on her looks and willingness

to show her body – something that legitimate Hong Kong actresses would never

have done back then – but over the years she burrowed her way into the film

industry doing every kind of film genre imaginable (there is no stereotyping

actors in Hong Kong) and by the late 90’s she was not taking off her clothes

anymore and was making some terrific films. In fact her reputation grew so

much that Hou Hsiao-hsein used her in three films and she was chosen as the

Asian girl in distress in the first Transporter film. Now approaching forty,

she is still one of the more popular film actresses in China.