Kill Bill: So Far

From So Close

Tokyo: We Are Coming

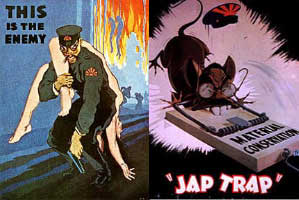

Only thirty years before the release of “Lady

Snowblood,” several million New Yorkers cheered a vast patriotic parade

that streamed up Fifth Avenue for eleven hours in June 1942. The

evident highlight was a float depicting a big American eagle swooping down

on a herd of yellow rats. As historian John Dower has observed in

War Without Mercy, this caricature captured the essential symbolic features

of racist characterization of the American stance toward Japanese people

– the strong individual versus an undifferentiated pack of vermin denied

any acknowledgement of humanity – an embodiment of the iconic image of

the yellow hordes of Asia.

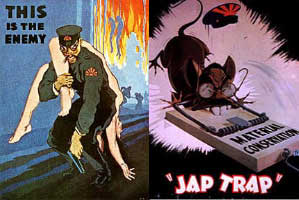

Abundant contemporary imagery of rats, insects,

monkeys or vipers was publicly invoked as justification for exterminationist

rhetoric advocating wholesale slaughter of the Japanese. “Rodent

Exterminator” was stenciled on helmets of many Marines during the 1944

invasion of Iwo Jima. The collection of body parts as trophies from

dead (and living) Japanese was so commonplace that personnel returning

from the Pacific theater were routinely screened for trophy possession

prior to embarkation. In 1943 the magazine Leatherneck published

a photograph of Japanese corpses with an uppercase headline reading “Good

Japs,” while the following year Life published a full-page photograph of

an attractive blonde posing with a Japanese skull. Another photograph

showed Japanese skulls as ornaments on American military vehicles.

Contemporary Japanese reaction was to view such material as indicative

of the American character. For their part, officially sanctioned

American perspectives endorsed notions that the Japanese were mad or crazy

with a perverse wish to die, and deserved the death brought to them by

Americans.

Until the 1960’s, American men’s pulp fiction

magazines blatantly co-mingled World War II propaganda imagery of the Japanese

with depictions of successively demonized Asian adversaries – Koreans,

Chinese, and Vietnamese – to invoke an all-purpose stereotype of an undifferentiated

mass fundamentally unworthy of life. Numerous war movies during and

since Word War II have portrayed the mass killing of people who had been

rendered less than human in this manner.

Perhaps most tellingly, the locus of these

devices in the fears and needs of predominantly white America is suggested

by Paul Verhoeven’s futuristic war film “Starship Troopers” (1997).

Verhoeven’s depiction of endless war against lethal “bugs” was deliberately

designed to engage the atavistic hatreds of so many Hollywood Pacific War

movies. By the device of constructing the enemy of the young (mainly

Caucasian) heroes as large, lethal insects, Verhoeven was able to examine

the genocidal corollaries of racial hatred during war, including the attribution

of lack of pain, individuality, conscience or any other human quality to

the demonized, bug-like enemy.

Postwar Hollywood also peddled the stereotype

of the soft-spoken, demure “Lotus Blossom” as emblematic of Japanese women

as well as the “Dragon Lady” of film noir. White actors continued

the practice of “yellowfacing” (playing Asian roles) until quite recently

– including Sean Connery in “You Only Live Twice” (1967) and David Carradine

in the 1972 television series “Kung Fu” – suggesting that Caucasians could

appropriate the requisite physique and role. Both stage productions

and film noir perpetuated portrayals of Asia and Asians as the object of

limitless fantasy and danger, involving opportunities for “exotic” romance,

miscegenation or fear.

Postwar Hollywood also peddled the stereotype

of the soft-spoken, demure “Lotus Blossom” as emblematic of Japanese women

as well as the “Dragon Lady” of film noir. White actors continued

the practice of “yellowfacing” (playing Asian roles) until quite recently

– including Sean Connery in “You Only Live Twice” (1967) and David Carradine

in the 1972 television series “Kung Fu” – suggesting that Caucasians could

appropriate the requisite physique and role. Both stage productions

and film noir perpetuated portrayals of Asia and Asians as the object of

limitless fantasy and danger, involving opportunities for “exotic” romance,

miscegenation or fear.

As Jeff Yang, Dina Gan and Terry Hong have commented

in Eastern Standard Time, Western popular cultural products have been frequently

so damaging in their depictions of Asians, even when not explicitly seeking

to be so. Against such a recent background of extremes in cultural

representation, ranging from literal characterization as subhuman vermin

(rats, snakes, insects), through absence (“yellowfacing”) to the false

exoticism of “Orientalism,” contemporary American film depictions of conflict

with Japanese people should tread carefully on controversial ground.

Scott Hicks’ “Snow Falling On Cedars” (1999) has certainly managed this.

“Kill Bill” has not.

As Jeff Yang, Dina Gan and Terry Hong have commented

in Eastern Standard Time, Western popular cultural products have been frequently

so damaging in their depictions of Asians, even when not explicitly seeking

to be so. Against such a recent background of extremes in cultural

representation, ranging from literal characterization as subhuman vermin

(rats, snakes, insects), through absence (“yellowfacing”) to the false

exoticism of “Orientalism,” contemporary American film depictions of conflict

with Japanese people should tread carefully on controversial ground.

Scott Hicks’ “Snow Falling On Cedars” (1999) has certainly managed this.

“Kill Bill” has not.

Among the problematic associations suggested by

“Kill Bill,” two in particular stand out when considered in relation to

the above history of racist characterization of the Japanese. The

first involves the conspicuously collective, dehumanized, mass death of

the Japanese “Crazy 88” gang at the hands of a single, brightly clad, blonde

Caucasian. Film and cultural critic Armand White has described the

death of Vivica A. Fox’s character “Vernita Green” in “Kill Bill” as butchering

by a white woman that continues white supremacist patriarchal film conventions.

Much the same could be said about the deaths of so many Japanese characters,

with the additional problematic that they wear masks and are collectively

labeled “crazy” (the “Crazy 88” gang) – devices reminiscent of wartime

notions of the Japanese as an undifferentiated mass of suicidally crazy

lesser beings. The solitary eagle scatters a pack of rats.

A second, related problem concerns the triumphal address by Thurman’s character

“The Bride” at the conclusion of this bloody combat. After surveying

the scene of carnage from above, “The Bride” announces that the wounded

survivors may leave but that their severed limbs remain hers. This

is reminiscent of the historical practice of taking body parts as battlefield

trophies. Historian John Dower has traced the roots of exterminationist

ideology against the Japanese to wars against Native American peoples during

the late Nineteenth Century. Perhaps the final scalping of “O-Ren

Ishii” in “Kill Bill” can be seen as part of this larger trajectory.

Among the problematic associations suggested by

“Kill Bill,” two in particular stand out when considered in relation to

the above history of racist characterization of the Japanese. The

first involves the conspicuously collective, dehumanized, mass death of

the Japanese “Crazy 88” gang at the hands of a single, brightly clad, blonde

Caucasian. Film and cultural critic Armand White has described the

death of Vivica A. Fox’s character “Vernita Green” in “Kill Bill” as butchering

by a white woman that continues white supremacist patriarchal film conventions.

Much the same could be said about the deaths of so many Japanese characters,

with the additional problematic that they wear masks and are collectively

labeled “crazy” (the “Crazy 88” gang) – devices reminiscent of wartime

notions of the Japanese as an undifferentiated mass of suicidally crazy

lesser beings. The solitary eagle scatters a pack of rats.

A second, related problem concerns the triumphal address by Thurman’s character

“The Bride” at the conclusion of this bloody combat. After surveying

the scene of carnage from above, “The Bride” announces that the wounded

survivors may leave but that their severed limbs remain hers. This

is reminiscent of the historical practice of taking body parts as battlefield

trophies. Historian John Dower has traced the roots of exterminationist

ideology against the Japanese to wars against Native American peoples during

the late Nineteenth Century. Perhaps the final scalping of “O-Ren

Ishii” in “Kill Bill” can be seen as part of this larger trajectory.

Other difficulties include the status of supporting

characters. Is Julie Dreyfus as “Sofie Fatale” intended to pass as

an Asian? Does Lucy Liu’s half-American “O-Ren Ishii” suggest references

to the continued American military presence and basing in Japan?

Is it necessary to depict the head of the Tokyo yakuza as half-American?

The prominence of non-Japanese in these key roles connotes a certain powerlessness

and possible cultural subjugation, while Liu’s “O-Ren Ishii” also strays

into the realm of the stereotyped “Dragon Lady” of Orientalist myth with

her sudden profanity and gratuitously immoderate violence. Even the

selection of poisonous snakes as codenames raises potential problems of

association with past usage.

Despite certain misgivings regarding its content,

many critics have nevertheless acknowledged the impressive visual staging,

spectacle and lush cinematography of “Kill Bill.” In Visual Intelligence,

Ann Marie Seward Barry has proposed recognizing a “New Wave” in action

film, termed the “New Violence.” This seeks to combine special effects

and visual aesthetics in ways that make violence both exciting and beautiful.

The marriage of brutality and aesthetically pleasing forms is especially

seductive, softening and “normalizing” the impact of the violence and may

even imbue it with sensuality. The resulting perceptual dissonance

can be heightened by certain technical features of filmmaking. In

shooting “Pulp Fiction” (1994), for example, Tarantino used extremely slow

film stock showing virtually no grain. This yields an unusually luminous

print allowing for depth of field and particular visual beauty. It

may be critically important to reflect on how the technical rendering of

a scene can deflect critical analysis of its content and narrative implications.

If the fight scene is “beautifully filmed” does this vitiate its barbarism

and possible political import? It should not, and the striking visual

aesthetics of “Kill Bill” also should not distract the viewer from its

reading possibilities.

Despite certain misgivings regarding its content,

many critics have nevertheless acknowledged the impressive visual staging,

spectacle and lush cinematography of “Kill Bill.” In Visual Intelligence,

Ann Marie Seward Barry has proposed recognizing a “New Wave” in action

film, termed the “New Violence.” This seeks to combine special effects

and visual aesthetics in ways that make violence both exciting and beautiful.

The marriage of brutality and aesthetically pleasing forms is especially

seductive, softening and “normalizing” the impact of the violence and may

even imbue it with sensuality. The resulting perceptual dissonance

can be heightened by certain technical features of filmmaking. In

shooting “Pulp Fiction” (1994), for example, Tarantino used extremely slow

film stock showing virtually no grain. This yields an unusually luminous

print allowing for depth of field and particular visual beauty. It

may be critically important to reflect on how the technical rendering of

a scene can deflect critical analysis of its content and narrative implications.

If the fight scene is “beautifully filmed” does this vitiate its barbarism

and possible political import? It should not, and the striking visual

aesthetics of “Kill Bill” also should not distract the viewer from its

reading possibilities.

Contemporary theories of spectatorship emphasize

reading strategies rather than constructed meanings. “Kill Bill”

may certainly have been directed and produced as a visually beguiling homage

to “grindhouse” cinema, but that does not limit the permissible reading

strategies. Technically sophisticated, it fails to deliver improvements

to the key narratives of Asian action cinema and ultimately loses their

threads. More troubling, the film also opens the possibility for

readings consistent with historical animosities and stereotypes.

It is not necessary to argue whether these were intentionally woven into

the narrative. Such reading strategies can readily be adopted whenever

the narrative fails to avoid continuity with certain charged historical

themes. Conventions of narrative and cinematic presentation may be

sufficient in their evocation of culturally repressed but not forgotten

themes of hatred and supremacy. It bears repeating that identical

acts performed exclusively by Asian characters (or exclusively on Caucasian

characters) would not raise such questions. They would be located

in a self-contained cultural space, and it seems imprudent to not recognize

this explicitly.

Contemporary theories of spectatorship emphasize

reading strategies rather than constructed meanings. “Kill Bill”

may certainly have been directed and produced as a visually beguiling homage

to “grindhouse” cinema, but that does not limit the permissible reading

strategies. Technically sophisticated, it fails to deliver improvements

to the key narratives of Asian action cinema and ultimately loses their

threads. More troubling, the film also opens the possibility for

readings consistent with historical animosities and stereotypes.

It is not necessary to argue whether these were intentionally woven into

the narrative. Such reading strategies can readily be adopted whenever

the narrative fails to avoid continuity with certain charged historical

themes. Conventions of narrative and cinematic presentation may be

sufficient in their evocation of culturally repressed but not forgotten

themes of hatred and supremacy. It bears repeating that identical

acts performed exclusively by Asian characters (or exclusively on Caucasian

characters) would not raise such questions. They would be located

in a self-contained cultural space, and it seems imprudent to not recognize

this explicitly.

(Click to continue)

All written material copyrights

by T. P. (2003)