In brief, “Kill Bill Vol. 1” emulates numerous classic Asian action narratives that invoke the avenging wrath of a solitary fighter. Familiar conventions include extreme loss and personal suffering involving immediate family as a backstory that self-evidently justifies retaliation, followed by a period of preparation leading to a climactic confrontation in which severe punishment is meted out to those responsible. During this transformation the protagonist may become progressively decontexualized – detached from or violating current customary relations and conventions. Unlike many Hollywood action conventions in which the protagonist’s acts are justified by delegated official power or ultimate restoration of the patriarchal order, Asian action narratives have frequently emphasized the antecedent nature of obligations – a debt of honor to deceased individuals or vindication of the self. Hollywood action conventions generally involve re-affirmation of patriarchal power and resultant order as a narrative resolution. Asian vengeance conventions may explicitly violate these in the service of personal honor.

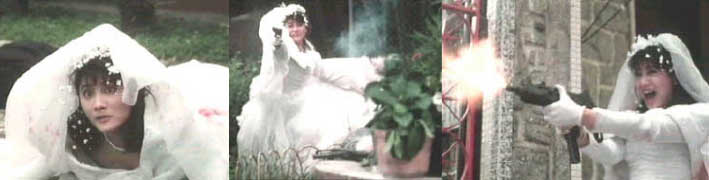

Superficially, this vengeance model resembles that adopted for “The Bride” (aka “Black Mamba” – Uma Thurman) in “Kill Bill.” The killing of her wedding party (a common HK device as seen in Chris Lee Kin Sang’s film “Queen’s High,” 1991), loss of her unborn child, her own attempted murder and extended coma establish powerful motivation. “The Bride” creates a list of those responsible – a group of predominantly female assassins headed by an unseen male controller (“Bill”) – and begins to kill them.

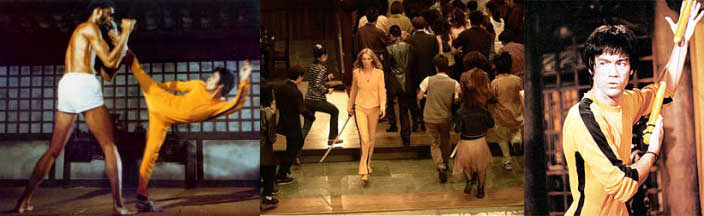

Beyond this initial similarity, “Kill Bill” diverges from the well-established generic conventions of Asian cinema in several critical ways. Honor-related vengeance by female fighters in Asian action genres both exacts and reaps a terrible toll. The protagonist often appears psychologically as well as physically reduced – losing every remaining asset and source of support. The personal price of vengeance is thus very high – often as high as the cost of the initial harm. This perhaps invites a philosophical reading of the relevant tensions and balance. “The Bride,” however, experiences no doubts, little suffering, and no additional costs. The bulk of “Kill Bill” is set in Okinawa and Tokyo where “The Bride” first has the perfect katana forged for her by Sonny Chiba’s sword maker before donning the yellow tracksuit of Bruce Lee Siu Lung (in “The Game of Death,” 1978) to assume the mantle of the invulnerable martial artist. By these devices “The Bride” self-consciously appropriates each of the greatest symbols of Asian martial arts. Far from suffering in her quest for vengeance, she instead becomes the greatest martial artist imaginable.

These references matter precisely because they will be noted by viewers familiar with Asian action cinema but may be missed by others who read “Kill Bill” as a representative homage. By the appropriation of such extremes of skill – also extending to rapid recovery from paraplegia by force of will alone, and fluent mastery of Japanese – “The Bride” does not operate within the conventions of Asian female vengeance films. Despite the obvious and frequent references to “Lady Snowblood,” “The Bride” is less like “Yuki” than an attempt to emulate Bruce Lee. In his films, and other generically similar narratives, vengeance is used as plot device to establish context and motivation before rapidly dropping away as the film showcases genuine martial arts virtuosity. Viewers accept the plot conventions and narrative limitations in return for the spectacle of the martial artist’s genuine skill. The same is also true of “Girls With Guns” films. Either the action choreography and martial artistry is spectacular – albeit too brief – or the emotional violation and response are compelling. In either instance, the spectacle is one of combined skill and excess – either of physical martial arts talent or transgressive emotion. Unfortunately, “Kill Bill” offers neither and thereby misses both key defining elements of Asian action cinema.

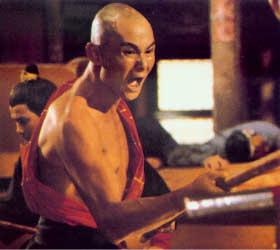

Viewers are not watching outstanding martial artistry, but instead are presented a familiar combination of computer graphics, wirework and constructive editing that supposedly can quickly dispatch Gordon Liu Chia Hui. Since “The Bride” is presented as an unstoppable killing machine, there is little dramatic tension either. Protagonists suffer and die in Asian action cinema. In “Kill Bill” only the designated enemies do so. A surfeit of exaggerated physical violence combined with the absence of emotional identification with the central character effectively desensitizes the viewer and vitiates any dramatic tension the piece initially marshaled.

By the time “The Bride” finally confronts “O-Ren Ishii” (Lucy Liu) in the film’s climax, the preceding gratuitous slaughter of her friends, associates and aides who include Julie Dreyfus, Chiaki Kuriyama and Gordon Liu, together with her character’s backstory, establishes a more imminently convincing vengeance motivation for “O-Ren Ishii” herself. At this point the film, in effect, pits a Bruce Lee surrogate (Thurman in the yellow tracksuit) against a Meiko Kaji surrogate (Liu in a white kimono). When the haunting theme music of “Lady Snowblood” (sung by Meiko Kaji) and the Japanese garden with softly falling snow (apparently inspired by the ending scenes of “Lady Snowblood”) are added to the mix, where is viewer identification directed? This collision of generic conventions seems deeply unsatisfactory since it fails to provide a point of emotional engagement. Asian action films constitute genres of excess, but not indiscriminately so. “Kill Bill’s” excess is a whole less than the sum of its parts, since one element tends to nullify others. The remainder is an excess of exaggerated violence. Is this, truly, the irreducible essence of Asian action cinema?

All written material copyrights

by T. P. (2003)