More than thirty years after this film was

released in 1967, King Hu’s Dragon Inn is often remembered more today for

being the inspiration for Tsui Hark’s 1992 remake than for its own merits.

Part of this is caused by changing cinematic tastes – but in this case it

is largely due to the original film being so difficult to find. This is a

shame because the original is certainly the more important film from a historical

perspective (and it could be argued a much better film as well). In a sense

it began the modern day wuxia film that directors such as Tsui Hark and Ching

Siu-tung were to build upon a generation later. There were earlier examples

of wuxia – Hu’s own Come Drink With Me and The Jade Bow, but Dragon Inn captured

the imagination of the movie going public unlike any other and became a huge

hit throughout South East Asia.

As Stephen Teo writes in Hong Kong: The Extra Dimension it “created in its wake a new trend in the martial arts genre. Hu’s style was imitated and swordfighting knight-ladies and all-powerful eunuchs became stereotypes in the genre.” The tremendous popularity of wuxia films lasted for only a few more years until the kung fu films replaced it as the audience favorite – but in the early 1980’s it was resurrected by Ching (Duel to the Death), Patrick Tam (The Sword) and Tsui (Zu Warriors). The popularity of this genre has come and gone a few times (at one time in the 1930’s it was even banned) – its zenith was perhaps in the early 90’s with the Swordsman Trilogy and a spate of imitations. Recently, its popularity has of course gone worldwide with the release of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.

After Come Drink with Me in 1965, Hu had

a less than amicable parting of ways with the Shaw Brothers and went to the

Union Film Company in Taiwan. He soon began work on Dragon Inn and put together

a cast of actors that he was to use in a number of his future films – Pai

Ying, Hsu Feng, Han Yingjie, Shi Jun and a number of character actors. He

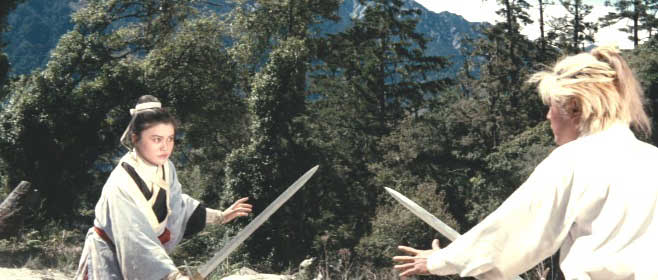

wasn’t able to use his knight lady, Cheng Pei Pei, from Come Drink with Me

because she was contracted out to the Shaw Brothers. So instead he chose

a very young (seventeen years old and her first film) Polly Shang Kwan to

be his martial arts heroine.

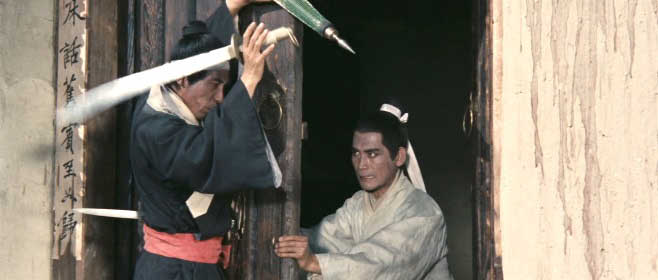

Hu had employed Han Yingjie for the action

choreography in Come Drink with Me and brought him on for this project as

well. For Dragon Inn, Hu told Han that he wanted the fights to be almost like

dance. To the modern eye – used to the fast and furious pace of modern HK

action films – the action in Dragon Inn may seem slow and plodding – but

Hu was as interested in the inherent drama of the fight as the fight itself.

In many of his fight scenes the contestants will clash – then step back –

discuss the situation – look for resolution or bait each other – then clash

once again. The sword fights themselves tend to be very operatic – swords

held high – long graceful sweeps or short forceful thrusts. The victim will

stand motionless for a moment – the film comes to a near stop – until he

plummets to the ground. The rhythmic percussion of Chinese Opera instruments

relentlessly drives this action. His action tended to be much less bloody

than many of his contemporary directors (Come Drink with Me being an exception

with it’s obvious Chambara influence) – and sometimes the camera even turns

away from the deathblow to return a second later after the deed has been

done. Again it is the drama of the kill that interests Hu – not the exploitation

of it.

The plot of this Dragon Inn is very similar

to Tsui’s - though the mood of the film is vastly different – darker

– more serious in tone – no body parts being served as entrees or strip fu

duels between women. The year is 1457 during the Ming Dynasty and the high

eunuch Cao Shaoqin (Pai Ying) has had the Minister of Defense, Yu, executed

and his children exiled to the far away frontier outpost of Dragon Gate.

Cao Shaoqin becomes concerned that the children will return some day for

revenge and so sends his spies of the Eastern Agency to wait for them at

a local establishment on the way to the outpost in order to kill them. Hsu

Feng plays the daughter – and though the part is very small - apparently

Hu took a liking to her and she became his main actress for most of his future

films.

The spies of the Eastern Agency arrive at

Dragon Inn and wait for the children to show up – but first a stranger appears

(Shi Jun) and calmly orders dinner. The spies are undercover – and try to

kill the stranger – but he slowly reveals his great martial arts abilities

- by holding poison in his mouth – spinning a bowl of noodles across the room

– catching a thrown knife with his chopsticks. More reinforcements show up

– but they pull back cautiously from this unexpected adversary to wait for

a more opportune time – but meanwhile two more itinerant travelers come to

the inn - Polly and her brother. It soon becomes clear that the strangers

have all come for a reason – to protect the children of the minister against

overwhelming odds. They may be small in numbers but all of them are superb

martial artists – which Hu quickly establishes with a few camera shots and

displays of agility - and willing to die for a cause.

This film is not only an important film – it is also a very entertaining film – full of courage, heroism and sacrifice – themes that were important to Hu. I did not find it quite as exhilarating as Come Drink with Me or as powerful as A Touch of Zen – but it is a wonderful film.

My rating for this film: 8.5

Among all of the Hong Kong directors, King Hu is my personal favorite. The reason is simple. He was the only man who did nothing to defame the Chinese society or Chinese culture --- in his works we find no triads, harlots in Cheung-sam, drug dealers, nerve-racking gunfights or battalions of vampires. Instead, we have the essence of Confucianism and Zen Buddhism.

In 1449, Emperor Ying T'sung was captured by the Tartars in a battle, and Defense Minister Yu Ch'ien proclaimed Ying T'sung's brother emperor and defeated the Tartars a year later. Ying T'sung was released by the barbarians and with the aid of a eunuch named Tsao Shao T'sin (played by Pai Ying) and Shi Heng, the Marquis of Wuching, he launched a coup d'etat and resumed the throne in 1457.Yu was beheaded and his sons were exiled. They were sent to Xin Jiang, and would inevitably pass through a place named 'Dragon Gate'. The ruthless Tsao Saho T'sin sent a team of Jin Yi agents to assassinate the children at Dragon Gate, however, they were rescued by a scholar who showed brilliant swordsmanship (played by Shi Jun) and a mysterious swordswoman (Polly Shang Kwan in her most legendary role). Finally, Tsao himself was killed and the children were saved. In real life, Tsao was accused of treason and put to death by the emperor himself----like most of his predecessors and successors.

It was a simple story told in a straightforward manner. Like most of King Hu's films, it has the following characteristics:

The use of an Inn

An ancient Chinese inn on a piece of barren land

was a very dramatic situation where all kinds of conflicts can break out.

In Dragon's Inn, this is the place where the heroes waged a sacred war against

the evil power. On the other hand, such a narrow and shallow space can be

used by the director to focus time and space into one phase. Another reason

for Hu to choose an inn is that this is a place where all sorts and classes

of people meet --- eunuchs, officers, swordsman, hawkers, hermits and spies

can stay in the same drawing room. Hu can thus create a miniature of traditional

society in an inn. Besides, only under such an occasion could a powerful

eunuch possibly be slain.

The heroine dressed in male costumes

The leading ladies in most of Hu's work dressed themselves as males. Their relationships with their male comrades are vague---- they were neither husband and wives nor lovers. They were professional killers and had no interest in love or sex. They were purely 'comrades' and it seems that both sexes have to suppress their sexual desires. Look at Tsao, he was powerful and keen in swordsmanship, but he was a EUNUCH. It seems that he tried to avenge his castration by corrupting the country. Hu has always suggested that sexual desire may corrode one's martial abilities, and as a semi-Zen-Buddhist, he tried to explore the idea of ' The World is Void ' -----so is sex.

Influence of Peking Opera in Hu's films

In his films, one can always tell whether a guy

is good or bad at the first sight. This is due to the Peking-Opera styled

make-up adopted by Hu .In Peking Opera, there are only five types of characters

and therefore Hu also tends to filter thousands of characters into a few

typical ones. All characters in Hu's films were one-dimensional and their

character was shown by their outward appearance. Basically, all of them had

a purpose to life, but none of them had bones and flesh. The director used

them as puppets to represent good and evil.

All of them kept on walking and running all the time, why?

The swordsmen and their comrades kept on moving, in search of freedom and their own destinies. What King Hu has always stressed that Zen, Confucianism, the fate of China, Chinese politics, history and myths, were only superficial themes of his works. They were only used to support his storyline, the real yet insinuated theme is the search for enlightenment, and the freedom of the soul. However, I don't think these swordsmen can succeed. They only fought against the secret agents, not against the emperor himself or his tyranny. They were sort of like Robin Hood, who was always loyal to the Imperial house. They did not understand that monarchy and feudalism itself was the root of all their sufferings. No matter how corrupt and vicious the government was, they wouldn't overthrow it. They would only kill one or two villains who were actually only lackeys of the Emperor. This is why they went into exile alone at the end of the story. Another important aspect of this sense of motion is that in Hu's film, since the story is so simple, the motion of the characters itself can be considered as part of the film's content.

The almost almighty villain

Villains, especially the chief villain, were also

depicted as formidable swordsmen. Look at Tsao, look at his might. Our swordsmen

have to use all their wisdom, courage and strength, plus the sacrifice of

many, in order to overcome him. Tsao Shao T'sin was the first villain in

Chinese film history to be depicted as a 'superman' who has gone to the wrong

side. His image was copied countless times later.

Apart from all these interesting characteristics,

Dragon Inn is an almost flawless cinematic piece. The storyline is simple

and clear. The cinematography was poetic and exhilarating. King Hu' s knowledge

of Chinese cultural history was shown by the authentic sets ---- they were

so real as if they were antiques. King Hu must have studied thoroughly the

costumes, weaponry and furnishings of the Ming period. I almost felt that

I was really watching people of the Ming dynasty fighting upon the screen.

In his first wuxia film, Come Drink With Me (1966), King Hu showed too much

Japanese influence and the film reminded me of Yojimbo (1961,Akira Kurosawa).

In Dragon Inn, everything is purely Chinese.

Finally, I would like to say something about the choreography. Although it was not as provocative as that in Tsui Hark's works, the choreography of this film, influenced by the Peking Opera, showed clearly the difference in different people's abilities in martial arts.

I would like to make a salute to Mr.Hu, maestro of Chinese cinema who was sacrificed by the over-commercial society of Hong Kong.

My rating of this film : 9

It's common knowledge that Tsui Hark's Dragon Gate Inn 92 was meant

as a paranoid allegory with the titular inn serving as a substitute for Hong

Kong itself being threatened and eventually ransacked by brutal exterior

forces and that it's boss (Maggie Cheung's unscrupulous, mercenary and fun-loving

character) was serving as a stand-in for Hong Kong’s similarly minded inhabitants.

In China the tradition of using art to pass subtle or not so subtle hidden/subversive

messages is almost as old as the country itself. A large bulk of the nineties

martial art/ swordplay revival had similarly thinly veiled subtexts and so

in it's own peculiar way did the original Dragon Gate Inn classic by master

filmmaker King Hu dating back from 1967.

Period films have always been shaped by and in some ways have reflected

the contemporary time in which they were made. Since the nineties, swordplay

films reflected the angst-filled anxieties brought about by the impending

handover of Hong Kong to China. But what the first Dragon Inn reflected in

the China of three decades ago was quite different. Back then after all Mao

Tse Dong was still alive, his cultural revolution running amok throughout

the country and Hong Kong itself was a red-hot kettle of social and economic

change on the verge of exploding. Finally, let's not forget that Dragon Inn

wasn't even a Hong Kong production to begin with but an entirely "made in

Taiwan" film. At its release Dragon Inn became a phenomenal run away

hit over the whole of South-east Asia, the very first regional production

to outdo the Hollywood-made imports. What was it in the movie that caught

the viewer’s imagination that made it such a success? As the era itself and

it's social and political context is long gone, it's the intent of

this piece to take a revealing peek and explain the surprising context and

subtext of this great film.

THE DOUBLE SEVEN CONNECTION

Way back in 1975 King Hu once explained his interest in the Ming dynasty, and where he picked up some of his ideas for Dragon Gate Inn.

"It's a particularly controversial period …< >…. there was a much discussed book by Wu Han about Ming politics. It was on the one hand the period when Western influences first reached China; on the other, it was one of the most corrupt periods in Chinese politics. Most of the Ming emperors were bad; some were drug addicts, some were very young indeed when they came to the throne. Power was effectively in the hands of the Court Eunuchs, who created their own secret services, the "Dong Shang or "Eastern Group". Without exaggeration, you could say that the power of the Dong Shang exceeded that of the German Gestapo. They could arrest and execute virtually anyone, including ministers of the Courts, without accountability or, indeed any legal process. Both Dragon Gate Inn and A Touch of Zen deal specifically with the operations of the Dong Shang."

So far so good, but it doesn't inform us of the possible connection between Dragon Gate Inn and it's contemporary subtext. It's at this point however that King Hu made this surprising revelation.

"At the time I made those movies, the James Bond films were very popular, and I thought it was very wrong to make a hero of a secret service man. My films were kind of a comment on that."

So was Dragon Gate Inn, a Chinese swordplay movie set in fifteenth

century Ming Dynasty China, an anti James Bond movie!? Apparently Hu

felt offended by the Bond's spy caper glorification of the murderous exploits

of someone above the law, so he did a movie, which, yes, featured an intelligence

agency but whose men were nothing more than ruthless assassins. "I didn't

like James Bond." Hu said on another occasion. "They made him such a super

hero but he was just an agent, a human being." With Dragon Gate Inn Hu did

a sort of spy caper of his own but inverted it, put it in a historical context

and somehow made it more realistic "It was a spy film, but the spies are

very human. I didn't want to glamorize them."

THE EAST IS RED

Beyond the James Bond connection, King Hu never admitted to any other contemporary subtext. What Hu omitted to mention in his interview though, others have pointed out. That Wu Wan the writer/historian whose writing initially attracted Hu’s attention towards the Dong Shang in the first place became on the eve of the infamous Cultural Revolution one of the first victims of Mao Tse Dong's persecution. He was targeted for having written a play set in the Ming dynasty, where a courtier chastises an emperor, a thinly veiled reference to an actual occurrence between Mao and one of his top generals during the disastrously managed Great Leap Forward of the late fifties/early sixties (which had brought a famine causing the death of up to 30 to 40 million Chinese). It's considered that Wu's persecution was the key event that prompted King Hu to do a film with a loyal minister and his family being persecuted by an all-powerful tyrant who is surrounded by devoted followers (the same as Mao's Red Guards) and whose very appearance is even evocative of Mao’s own.

THE WHITE TERROR

Both the James Bond and Mao/cultural revolution connections are acknowledged

parts of Dragon Inn’s subtexts by film scholars. The following idea though

is entirely this writers own, who speculates that the secret service element

may also have been equally prompted by Taiwan's Republic of China’s own infamous

intelligence agency. For despite being called a "Republic", Taiwan was actually

a ruthlessly fascist-like one party state. Every square inch of the country

was under the watch of the secret service, the "Kuo-Tang Ming" regime watchdog,

who were not only into spying but passing disinformation, intimidation, and

torture - even political assassination. Chased away by the Communists

back in 1949 and taking refuge in Taiwan, the Kuo-Tang-Ming forces forcibly

took over the island and conducted an utter purge of it's native political

and cultural elite which is said to have been more than 40,000 victims.

Taiwan then stayed under martial law for almost four decades during which it was subjected to a ruthlessly conducted anti-communist white terror campaign. It is quite telling that in the late seventies, well after Dragon Gate Inn’s release, the whole family of one of Taiwan’s opposition leaders was murdered in their sleep by a still unknown party. Then in the early eighties the secret service dispatched a triad hit squad to the USA to silence a Sino-American writer who had dared to write an unflattering biography of Taiwan’s then premier. Or that the wife of Taiwan’s current premier, a former opposition leader, was made a wheel chair bound invalid following a still unsolved car assault made in 1985 - at a time when the regime finally started to release it's iron grip.

Now unlike the Bond or Mao subtext, there is no obvious track leading

to a Taiwan/Dragon Gate Inn connection and King Hu was quite new to Taiwan

when he came to make movies after spending twenty years in Hong Kong. Still,

the Dong Shang depredations as described in Dragon Inn fits the sort of activities

of an above the law Gestapo like secret police such as existed in Taiwan.

And the heavy atmosphere of fear, suspicion and duplicity does also fit the

sort of society Taiwan must have been like under martial law. Yes, King Hu

was a newcomer but not politically naive, and he must have recognized very

quickly the island society for what it was, one of fear and whispers where

the wrong words or the wrong act could result in imprisonment, torture and

death. Under such circumstances it's hard to imagine that King Hu was not

influenced in some way, although he remained careful to cover his tracks

in order to avoid any trouble with Taiwan’s strict censorship laws.

A TOUCH OF CHINA

In Dragon Inn the Yu children are sent in internal exile to a far removed

frontier outpost. This was a customary form of punishment in ancient China

though more for common criminals than disgraced officials and their family.

It was considered a fairly dreadful punishment, as it meant that one would

be cut off from China's civilized world to live in a remote, hostile and

all too alien territory. Exile was also the fate of the Chinese living

outside the motherland in the British colony of Hong Kong, Taiwan or south

Asian countries; whether they were migrants, refugees or even stranded visitors

caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. This was certainly true for

King Hu, as he found himself stuck in Hong Kong when the frontier with the

Mainland was closed down shortly after the Communist victory. Exile is not

really part of Dragon Inn’s drama, or at least not much of it, but it's undeniably

part of the film's context for it is King Hu’s life as an exile that brought

him to make films painstakingly recreating ancient China and conjuring-up

it's ancient classical culture. It was the evocation of ancient mythical

China that seized the exiled Chinese viewers imaginations when Dragon Inn

was released.

It tentatively rekindled a broken link for those who had or were forced to leave the motherland behind and gave a "touch of China" to their children, those who had left too young or were born outside of it. "People like me" once said Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon director Ang Lee in a tribute to King Hu following his death in 1997, "who grew up in Taiwan, receiving a Chinese education, have lost touch with the Mainland. Because I was brought up as a Chinese but I haven't really been to Mainland China. That's why I sometimes feel strange about my Chinese identity. This identity was obtained from Mr Hu’s movies and from TV and textbooks. It was very abstract, not because of blood relationship or land but rather an ambiguous cultural concept. It was like a dream. You couldn't make sense of everything, but it was a Holistic Chinese influence and it's in my blood".

PORTRAYAL OF VALOUR

So in the end King Hu's Dragon Gate Inn was just as anchored in the reality of it's days as the 1992 version was. Unlike Tsui Hark though, who made his film into an obvious outlandish allegory with it's politics on it's sleeves, Hu took a much more subtle and haunting approach gracefully brushing like an "evocation" the Chinese peoples tragic condition of endless tyranny, oppression and exile. But that's only the first part of the picture, the tales set-up, for afterwards Hu made Dragon Inn into a "heroic fantasy" with it's valiant heroes taking a stand against ruthless oppressors, challenging them, mocking them even. Something a common Chinese could only dream of.

MAGNIFICENT DRAGON

Released in Taiwan in 1967, then the following year in Hong Kong, Dragon

Gate Inn became a ground-breaking hit that attracted viewers for it's thrilling

action, suspense and drama, it's outstanding cinematic quality, and no doubt

because it captured with such grace and poignancy both an image of mythic

ancient China as well as the inner pain, longing and desire of the Chinese

people themselves. Dragon Inn’s success assured that King Hu’s cinematic

approach would be imitated by a slew of directors and also gave Hu the commercial

clout to make an even more visionary and ambitious work. Unfortunately, by

the time he had finished Touch of Zen three years later, the south-east Asian

viewers attention had moved to the more visceral, and angst-filled power

of the budding kung fu cinema of Wang Yu, Bruce Lee and Chang Cheh. Although

Hu would make a handful of truly outstanding martial art pictures during

the following decade all would have mild or disappointing receptions at the

box office. So Dragon Inn would sadly turn out to be quite a unique event.

Still it happened at such a crucial moment in history as to make it even more magnificent and precious than any other box office triumph ever. Indeed in 1967 Mao had triggered his Cultural Revolution, Wu Han the man whose writing and persecution had inspired King Hu was left to die in jail and an entire generation of young Chinese were taught to denigrate their own culture, some even actively seeking to destroy it. Yet outside of China there was this movie Dragon Gate Inn that was giving a taste of mythical China and creating a connection between young exiled Chinese and their Motherland. There can be no greater testimony to the endurance of Chinese culture and the power of King Hu’s cinematic vision than this.

SOURCES

Rayns Tony. Director King Hu. Sight

and Sound NO:?

Rayns, Tony. Laying Fondations Dragon Gate Inn.

Cinemaya 39-40, 1998

Richard James Havis King Of Sword, Kamera. (internet)

Transcending the Times: King Hu, Hong Kong.

Urban City Concil 1998.