Reviewed by Yves Gendron

Contrary to what many are likely to believe, the film that redefined seventies HK cinema was not a kung-fu movie by either Bruce Lee or Jackie Chan but the screen adaptation of a vaudeville oriented stage play set in an impoverished tenement location; THE HOUSE OF 72 TENANTS. Produced by the Shaw Brothers, it featured a bevy of their stars and was directed by Chor Yuen, one of the best HK filmmakers of the sixties and seventies, and it was a phenomenon that broke box-office records and struck a deep cord with the local public in a way few movies ever done before or since. While not really revolutionary in itself, the film’s inspired use of the local Cantonese dialect and of burlesque comedy led to a series of initiatives within the HK film industry that radically changed its outlook and set it off on a whole new path. In other worlds, HK cinema would have probably evolved in a very different way than it did if it hadn’t been for HOUSE.

For all its great box-office success and its crucial role in the local film scene, HOUSE has remained a fairly obscure movie for most Westerners. This is hardly surprising given that the film’s vaudeville influence and the local flavor would have attracted little interest for a non-Chinese audience. It didn’t help either that the film remained unseen since its initial release in the early seventies, hidden away inside the Shaw Brothers vault as most of their movies were. So for nearly three decades HOUSE was but a title mentioned in Hong Kong cinema’s literature or a memory locked inside the heads of an older generation of viewers.

This long hiatus in limbo came to an end though when the Celestial company started their great task of releasing restored Shaw Brother movies on DVD with HOUSE being among the first batches being sold. Since then westerners as well as a young generation of HK viewers have finally had the opportunity to see and judge for themselves this long hidden watershed film which brought about one of HK cinema’s most remarkable turning points.

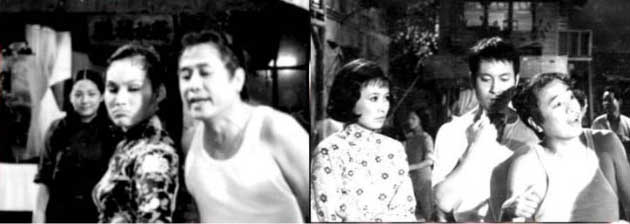

Life is hard for the inhabitants of a poverty row tenement who have to go through not only a harsh economic depression, but also the petty abuses of both their landlady, the feisty Pak Ku (Hu Chin), and her arrogant husband Bing (Tin Ching). It doesn’t help that the later makes frequent use of his crony, the corrupt and buffoonish street cop 369 (Lau Yat-fun), to create further difficulties for them. Thankfully, the righteous spirit of young, chivalrous cobbler Fat Choi (Yueh Hua), the quick wit of snack-food street-seller, Ah Fok (Hoh Sau San), and the deep sense of solidarity between the tenants themselves helps them through their lot and even at times to get back a bit at their tormentors. When, however, Pak Ku wants to sell her stepdaughter servant, the lovely Ah Heung (Cheng Li), the tenant’s resourcefulness is going to be pushed to the brink. Will they be able to prevent the dastardly deed?

From the Shanghai stage to Shaw Brother’s studio: THE HOUSE OF 72 TENANTS journey.

THE HOUSE OF 72 TENANTS was originally a stage comedy created in Shanghai in 1945 and set in that city. At some point it was staged in the Southern city of Guangdong near Hong Kong and then it played in the British Colony itself. A first screen adaptation was also produced in the Mainland in 1963. HOUSE belongs to what can be described as the “tenement” genre - productions which were on stage or on film and set in a shabby-like location showing a small community trying to survive in dire economic circumstances. At times, they took on a direly dramatic shape and were an indicting socio-political statement, as in the 1994 film CAGEMEN for example. At other times though, through a mix of pathos and comedy it could present a dignified portrayal of down trodden people showing their indomitable will to carry on and help each other in a poignant affirmation of communal brotherhood. That is what happens with the second screen-adaptation of THE HOUSE OF 72 TENANTS. It was undertaken in 1972 at a time after the Colony’s economic boom of the sixties when it suffered though a severe (albeit relatively brief) bout of economic depression.

Given their heavy social subtext, tenement productions, either for the stage or the screen, were usually tackled by leftist oriented film companies. In an offbeat twist however, the early seventies HOUSE movie was initiated by none-other than the right-wing studio Shaw Brothers in association with the local TV channel TVB* . As Shaw specialized in non-controversial gloss escapist fare, this new version of HOUSE was accordingly made into an innocuous stellar-cast vaudeville losing no doubt some of the original play’s social-minded militant outlook. Top Shaw director Chor Yuen was handed the directorial duties. Shaw directors usually held a large degree of autonomy including the possibility of initiating their own projects, but it’s not known by this reviewer if the idea to make a new HOUSE adaptation actually came from Chor or if this was an assigned job. Regardless of who initially originated this though, since Chor Yuen handled the screen adaptation it can be fairly assumed that he had a sense of ownership over the film. In order to widen it’s viewership and maximise its box-office appeal, HOUSE was also made in two different dubbed versions; one in China’s lingua franca; Mandarin and the other in H-K own local southern dialect; Cantonese.

* Actually TVB was and is still is to this day, part of the Shaw brothers greater commercial empire but from a different branch separate of their movie making operation

A Galaxy of Stars

While not all of HOUSE’s seventy two tenants are shown, the film still has a rich gallery of at least three dozen characters big and small, shared in equal measure by Shaw and TVB’s large stable of stars, character actors and extras. Since Shaw had a glamorous star system, the most important roles went naturally to big name actors such as martial art player Yueh Hua, leading lady Cheng Li, beloved chubby comedienne Lydia Shum and popular TV host Ho Sau-san. Shaw also saw fit to have throughout the film another dozen of its stars and famed supporting players make cameo appearances. A gimmick influenced perhaps from such Hollywood all-star cast fare as AROUND THE WORLD IN EIGHTIES DAYS (56) and THE LONGEST DAY (66). Included among these faces were then newly establish martial art star Chen Kuan-tai as a righteous street cop as well as Shaw siren Lily Ho among others.

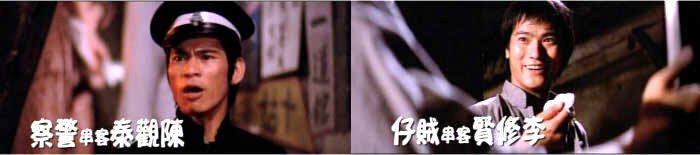

Shaw also displayed in the same way many of its then newly groomed talents and debutante starlets. Most actually never went beyond playing bit parts before fading into obscurity. Yet a couple did in time make a name for themselves such as future hard-boiled cop Danny Lee who makes a five second long appearance as a thief. There are also a handful of offbeat cameos such as the film director himself Chor Yuen who does a quick Hitchcock-like walk-on as another thief. This is only the tip of the iceberg though, for more exhaustive displays of HOUSE large cast and cameos (which include Chor’s own wife and infant son) check this review’s special annex; THE HOUSE OF 72 TENANTS stars gallery.

Regardless of whether they play a lead role or are just doing a cameo, each time an actor makes his initial entrance on the screen, Chinese script will instantly pop-up to name him and the part he plays. "Yuen Hua as Fat Choi" for example. This was a gimmick often used in Chinese and Japanese films in the seventies, early eighties and the early nineties, in particular for stellar-cast movies based on historical, literary or mythical lore. They are very useful in helping the viewers keep track of an often extended gallery of characters, but also provides a great way for a movie to flaunt its stars or to present new promising acting talent, which is exactly what HOUSE was doing with its stars/new names special cameo strategy. Where this trick comes from is a bit clouded but earlier variants of it are known to have been used back in silent movies, Hollywood movies of the thirties and forties as well as spaghetti westerns. Traditional graphic art as well as comic manga coming from both Chinese and Japan also use at time this peculiar gimmick.

Mercurial Director Chor Yuen

Until recently, Chor Yuen (or Chu Yuan as he is credited in the film; the Mandarin version of his name), would have only been recognised by HK Western film fans as the villainous Mister Ko in Jackie Chan’s classic POLICE STORY (86). Celestial’s gradual release of Chor’s Shaw opus made up mostly of swordplay movies may give the impression that he was a master martial-art filmmaker. Chor himself didn't see it that way, as he was one of the most prolific and mercurial directors ever seen in HK cinema. He started directing in 1958 by making Cantonese-dialect melodramas and romances. By the mid-sixties he was crafting caper comedies such as the now classic BLACK ROSE (65). Then toward the end of the decade he turned to social oriented melodrama, experimenting audaciously in cinematic forms and styles. He only started doing martial arts in 1970, and kept switching between genres for the first half of the decade; going from comedy to drama to martial arts, even an Opera film on at least one occasion. In making THE HOUSE OF THE 72 TENANTS he simply set his sights on adapting a popular socially minded vaudeville for the screen.

Even working with an already existing text, Chor Yuen’s abilities as a writer and director must have been put to the test. Just for starters he had to do a stage-to-film adaptation and was faced with the task of putting a cast of dozens of characters on screen without making either a stiff over-stagy spectacle or an incomprehensibly, loud and noisy mess. Pretty tricky. He had also to make broad, satirical comedy out of the harsh life of down trodden working class people, dealing with such hot issues as rampaging inflation, corrupt police, abusive owners, even the selling of children to slave labour and prostitution. And last but not least, he has also to adapt a Shanghai-originated play to a specific Hong Kong setting where the local people had their own peculiar idiom, culture and mentality.

Chor however did splendid work. The film is theatrical all right with the tenement courtyard acting as a stage substitute and the story is divided in a very clear series of acts but done with such an assured use of framing, close-ups, zoom-ins and movement as to create a cohesive, fluid and catchy ensemble. As a character driven film, there was precious little in the way of stylistic perks so as not to detract from the actors’ performances, yet some were used occasionally. Besides the pop-up script trick described above, one other was the use of freeze frames which close each act and Chor’s use of voice over to substitute for the actors theatrical asides.

It’s in the totally studio bound recreation of a Hong Kong working class urban neighbourhood, though, that HOUSE is most impressive and vibrant. Not so much in the sets themselves, which while lavishly detailed, as fitting a Shaw production, are still quite, un-naturalistic. Rather the film comes alive in the lively, buzzing of its people and the way they talk, joke, work, live and argue. Chor was thus proving himself superbly talented in creating a self-contained microcosm. A skill that he would bring to perfection in his later studio bound atmospheric swordplays like KILLER CLANS (76).

The Cantonese Connection

With HOUSE Chor was actually making the first true major Cantonese movie of the seventies. For if some Cantonese spoken films were occasionally shown, these were merely the dubs of Mandarin productions. At the dawn of the seventies Hong Kong native Cantonese speaking inhabitants were totally deprived of a cinema reflecting their own local culture and reality. It hadn’t always been that way. Back in the fifties and sixties the HK cinema industry had been divided along linguistic line; the Cantonese, which was the local language, and Mandarin, which as mentioned before was China’s lingua franca. Each of those cinemas not only made use of a distinct language, they had also their own favoured genres as well as a distinctive cinematic approach.

Thus Mandarin specialized in classy, sophisticated escapist fare like period pieces, musicals, lush melodrama and starting in the mid-sixties martial arts. As Mandarin was spoken in Taiwan, Singapore and by the Chinese Diaspora throughout the world, HK Mandarin cinema had a far wider market and was far wealthier than its Cantonese counterpart whose audience was limited to Hong Kong as well as some American Chinatowns. Far more restricted in its audience and therefore in its financial resources, Cantonese cinema – whose favoured genres were Operas, martial arts, social (melo)drama, and satirical comedies - tended to look more cheap and even shabby when compared to Mandarin films, but usually featured better acting and a more raw, spirited vibe.

For many years this status quo had coexisted up until the mid-sixties. Around that time an unfavourable economic situation, the arrival of Cantonese spoken TV in Hong Kong and the ferocious competition of the classier looking Mandarin films contributed to a sharp decline in the Cantonese film industry. Hopelessly outclassed and outmoded by its Mandarin rivals it finally totally collapsed in 1970, leaving the entire HK cinema field to one dominant Mandarin studio: the Shaw Brothers. By 1973, only a couple of true Cantonese movies had been made since the debacle. It is within that critical context that THE HOUSE OF 72 TENANTS entered the scene. Fittingly it was one of Cantonese cinema’s most talented directors who was called to make the film, Chor Yuen. Interestingly enough, HOUSE had many of the old Cantonese cinema’s chief characteristics such as a realistic sensibility, the use of farce and satire to tackle relevant social issues and the use of the local idiom to truly reflect both the living reality and spirit of the HK people.

The 72 Tenants Beating Bruce Lee

HOUSE was released on the 22nd of September and the film was a sensation as HK people readily recognised themselves in the film’s story and characters. Indeed, while the movie might be set in the past and at an unspecified location it had its actors speaking the local dialect and accurately displayed Hong Kong slang and smarts as well as its harsh, working-class surroundings. Heck, some characters even spoke Cantonese with a strong accent indicating their non-native origins. A neat realistic touch, as Hong-Kong had been a safe haven for decades with refugees coming from all over China. Although it showed the difficulties of living in the lower strata of urban society, the Hong Kong audience saw that HOUSE, through its comedic content and satirical edge, was not only recognising the challenge of working class people’s lives but was an ode to their indomitable spirit and pride, hence the film’s record breaking success.

HOUSE was released nearly two months after Bruce Lee’s death and two months before the release of his last film ENTER THE DRAGON. The latter film rose to become the second top local production of the year but still earned much less than HOUSE (3 ½ million to HOUSE’s near 6 million). Local audiences were still upset by the Little Dragon’s passing of course but it has been said that they also had not appreciated having their native son go Hollywood to make a most un-Chinese action-spy movie. On the other hand HOUSE was Hong Kong through and through and ended up remaining on screen for a whole month - twice as long as the usual HK movie run.

Bruce Lee’s sudden departure is widely considered to have created a void in Hong Kong’s martial art cinema. Actually, martial art cinema’s prominence was already slipping even before Lee’s death in favour of new fads such as sex comedies. His sudden passing therefore probably only precipitated an already nascent trend. Then HOUSE came in and its tremendous success was the catalyst for one of HK cinema’s major trend shifts in its history. Indeed HOUSE showed all too well that Cantonese was still a pertinent language to use, and that contrary to what was thought as common wisdom; a struggling working class story could make as much money as a great martial art epic. Chor Yuen though wasn’t the one who led HK cinema in that direction as he went on to tackle other film genres. Instead, a newly established leading comedian, Michael Hui, picked up the torch. He had his start in a string of Shaw movies but then moved to its main rival Golden Harvest which gave him the opportunity to write and direct his own movies; which turned out to be Cantonese spoken struggling every-man comedies. For the next several years to come martial art movies became only a secondary sub-genre, while a new Cantonese working class comedy cinema quickly developed under Michael Hui’s auspices with its own set of stars such as Hui’s brothers Sam and Ricky as well as Richard Ng. In time, martial art cinema also developed a Cantonese originated funny side thanks to Shaw martial film master Lau Kar-leung and such figures as Wong Yu, Mak Kar, Sammo Hung, Yuen Woo-ping and of course Jackie Chan, but that’s another story.

By the end of the seventies it was both the Cantonese language and comedy style that totally dominated the HK screen. Quite a reversal of fortune from the situation at the beginning of the decade - a change that can be directly traced back to the Shaw produced HOUSE. There is some bitter irony here for if Shaw hadn’t made this fateful film, a Cantonese revival might have only occurred at a much later date and Mandarin dominance might have continued for a while still and as said at the beginning of this piece H-K cinema history would have been quite different. Instead by the mid-eighties the long belated Shaw studio ceased its filmmaking activities at a time when Mandarin had been long gone from the HK screen.

Conclusion: It’s Comedy Tonight.

A thirty year old, studio bound vaudeville piece - the adaptation of a social-minded stage-play dating back from the forties - HOUSE at first glance wouldn’t look like the most appealing of movie prospects for most contemporary viewers - especially those born and bred on Stephan Chow’s machine-gun fast, nonsense comedy schtick. Granted that HOUSE is not nearly as riotous and frantic a piece as Chow’s and its most unlikely that a Westerner would ever appreciate the film in the way a HK native could. The linguistic and cultural gap is just too great. That said, far from being rustic and stagy, HOUSE is very much an engagingly catchy, delightfully enjoyable and quaintly charming comedy offering. Thanks to Chor Yuen’s smooth, fluid narration and filmmaking as well as the players dead-on, lively performances we get to quickly care for the endearing characters, frown at the villain’s misdeeds, smile at their much deserved comeuppance and either grin, giggle or laugh at many of the comic bits especially the fire-brigade infamous chant “Cash equal splash, No Cash no splash, You pay we spray, no pay no stay!” This is HOUSE’s biggest hoot and actually earned Chor some real life enmity with Hong Kong’s firefighters.

HOUSE is also enjoyable for the who who’s of Shaw Brothers players and the cameos it offers. It is quite an invaluable opportunity for a younger generation of viewer to get a fine introduction to Shaw and it’s players - most of who have long retired and some even passed on. Finally, let’s not forget its all too important historical role. Thus just as ONE ARMED SWORDSMAN in 1967 and A BETTER TOMMOROW much later on in 1986, HOUSE OF 72 TENANTS is one of those handful of movies which have altered the course of HK cinema. Furthermore, many have described Chor Yuen’s seventies swordplays as the missing link between the early modern swordplay of King Hu and the hyper kinetic wire-fu extravagance of the early eighties and nineties. The same is true for HOUSE but for comedy as the film could be properly assessed as the bridge between Cantonese sixties social satire comedy and HK’s struggling every man burlesque which is the foundation for Hong Kong modern comedy

After such an assessment it goes without saying that the film is most recommended, except for those who really don’t like old-fashioned vaudevillebroad comedy and the constant facial mugging.

Rating as a comedy: 8 but extended to 8.5 as a major seminal film piece.

Sources: Stephen Tao, Hong Kong The Extra Dimension.

Check out the Gallery of Actors/Characters here.