A Chinese Ghost Story 2

Director: Ching Siu-tung

Year: 1990

Rating: 8.5

“The story continues”.

So begins this terrific sequel to the influential

film that three years earlier had entranced the cinematic world with its

magical mixture of imagery, music, romance, special effects and the supernatural.

Once again Tsui Hark and Ching Siu Tung fill up the screen with a sumptuous

visual feast that is lyrically poetic and dreamily hypnotic. Like a vortex,

the film pulls the viewer into another world where anything is possible –

ghosts are unmasked to reveal heartbreakingly beautiful women, evil demons

surreptitiously suck the life force out of humans, men burrow beneath the

earth and fly above it by skateboarding on speeding swords and an impassioned

midair-swirling kiss can save your very soul.

The mood of this film differs somewhat from the first in a number of respects.

The first half of this film is surprisingly comedic in nature and has a number

of scenes that are slyly amusing – while the second half becomes a tale

of high adventure – a small band of heroes – trying to save the Kingdom from

evil doers. To some degree, romance and the supernatural take on a lower

profile in this story.

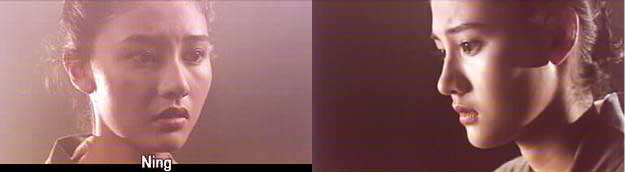

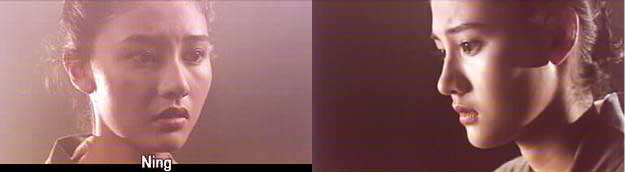

In what appears to be a few years after the first film ended, Ning (Leslie

Cheung) is still burdened down and heavy of heart by his passionate love

for Sian but he has sadly resigned himself to never seeing her ghostly image

again – “if she reincarnated, she would be a baby now”. He has returned to

the small town where it all began before, but it is now desolate and dangerous

as criminals roam the land. Bounty hunters mistake Leslie for a criminal and

throw him into jail where he is scheduled to be executed. An old bearded prisoner

helps him escape by showing him a tunnel through the wall (ala Alice in Wonderland)

and also gives Leslie an amulet as good luck. Tsui Hark perhaps makes a political

statement by having the old man refuse to escape because in jail he is able

to write whatever he pleases without fear of censorship or death.

On the outside, Leslie sees a solitary horse and thinking that the old

man had arranged it, jumps on it to escape. In the bushes taking care of

business is a young Taoist priest, Jacky Cheung, who goes after Leslie by

chasing him underground. They meet up at a deserted inn that appears to be

haunted and team up after being attacked by a giant demon monster. Here the

film indulges in a long but very funny routine when Leslie accidentally uses

a spell to freeze Jacky – but he doesn’t know the undoing spell and Jacky

can use only his eyes to try and warn Leslie that the monster is right behind

him. A bit of inside humor takes place earlier when one Canto-pop star Leslie

sings and the other Canto-pop star, Jacky, complains how bad it is and stuffs

paper into his ears.

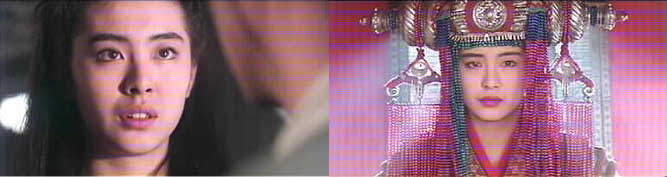

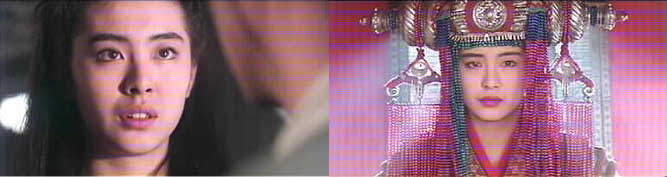

The two of them are also attacked by a party of tree swinging white clad

“ghosts” who turn out to be all too human. In a stunningly beautiful sequence

the mask is ripped off one to reveal a ravishing Michelle Reis (Moon) and

then another mask is removed to display an equally radiant Joey Wong (Windy).

Initially, Leslie thinks it’s his Sian come back, but he soon realizes that

Joey is flesh and blood and not his beloved. It turns out that Joey and Michelle

are the daughters of a high court official, Lord Fu (Lau Siu-Ming who actually

played the Tree Monster in the first film), who has been falsely arrested

for treason. They plan to rescue him.

Because of the amulet given to Leslie, the group of rebels mistakes him

for a legendary wise man, Elder Chu, (though the girls are quite confused

and attracted by his boyish good looks) and Tsui Hark again gets playful.

In perhaps a joke directed at film critics who read too much into a film,

the rebels search for hidden meanings in everything Leslie says or the poetry

that he recites – when in fact it means exactly what it says.

In any event, they all band together (joined at one point by swordsman

Waise Lee) to attempt to save Lord Fu from what turns out to be a monstrous

conspiracy led by the court eunuch (Lau Shun). It becomes so perilous that

Leslie has to find Wu Ma (the Taoist priest in the first film) and persuade

him to enter into the fight to save the Emperor. In the final fight – against

a giant centipede among other things – there is a large utilization of CGI

– which are not particularly sophisticated but quite fun.

Though this film is a complete pleasure to watch, it didn’t have quite

the weight or emotional impact of the first film. Or maybe I am just a sucker

for a love story between a human and a ghost – but I very much missed Sian

too.

One thing that struck me as intriguing is how the film is a partial throwback

to the HK films of the 50s and 60s in terms of its portrayal of the male character.

In these older films the man was often shown to be somewhat effete and more

of a thinker than action oriented – as exemplified in some King Hu films

such as Touch of Zen and Legend of the Mountain. There were even many instances

in which men in the movies were actually played by female actresses – Ling

Bo and Yam Kim-fai were two famous actresses who often did this. Then with

the advent of the martial arts films in the late 1960’s the “masculine male”

made a comeback in HK films. Chang Che who led this resurgence to a large

extent calls it “yanggang” in his essay in the book “The Making of Martial

Arts – As Told by the Filmmakers and Stars”. But here Tsui Hark – a traditionalist

in many ways - brings it back with the character of Ning. His character is

completely ineffectual and almost feminine – and like the proverbial damsel

in distress he is constantly having to be saved by either of the two women

or the (sexless) Taoist priests or just plain good luck.