By Mark Schilling

2007

Paperback

154 pages

$16

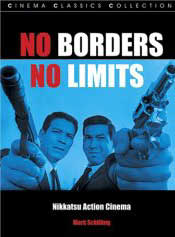

This is just a heads up for fans of older Japanese films to be on the lookout for this book. It covers a period and genre of films that hasn’t received much attention outside of Japan and has very little written about it in English. From the late 1950’s to the early 70’s Nikkatsu produced boat loads of action films full of tough guys, beautiful dames, jazzy scores and hard edged dialogue. During the peak years over 100 films were coming out a year, but by the mid 60’s the entire Japanese film industry went into decline and the Nikkatsu action films began a slow fade as well. It had a short rejuvenation in the early 1970’s with a move to a more hip rock action genre with the Stray Cat series but by 1973 the company had switched over completely to their pink film content.

Schilling is a well-known expert on Japanese film with his current job reviewing films for the Japan Times, his programming involvement in the Udine Far East Film Festival and two previous books. He clearly shows affection for these films as well as an extensive knowledge of them and the actors and directors responsible for them. He first wrote this book as an accompaniment to a Nikkatsu Action Retrospective at Udine and has now expanded it for publication. The book is broken down into five sections – a history of Nikkatsu, the major actors, the major actresses, a few of the lesser billed actors and a few of the main directors. There are also a generous amount of color poster images strewn throughout the book. It is well written and easy to get through and to someone like me who knew absolutely nothing about this period very informative. As nice as this is, I would have appreciated it even more if Schilling had added three more sections for the uninformed – one with reviews of a number of his favorite films, another comparing Nikkatsu action films to the action films the other companies were producing – what made the Nikkatsu films unique - and thirdly a helpful listing of which of these films are currently available with English subtitles.

This third point of course points out the frustration of reading

a book like this – as far as I know very few of these films are available

with subtitles – a number of the Seijun Suzuki films certainly and a small

smattering of some of the others such as Black Tight Killers. One positive

though is that this may be changing. Currently some of the films that showed

at the Udine Retro are slowly making their way around the United States

thanks to the endeavors of Subway Cinema’s Marc Walkow and Nikkatsu is

hoping to find a distributor in the states to take a package of these films.

That would be delicious.

Contemporary Japanese Film

By Mark Schilling

Paperback

399 pages

$25

1999

This is one of the few books in English that covers recent Japanese films without a specific genre focus such as yakuza, cult or a particular director. Schilling has been reviewing films for The Japan Times for some 16 years while living over there and has gained an enormous amount of knowledge on the subject and has written a number of books on Japanese cinema and culture. This is a fairly simple endeavor – to a large degree much of it was already written by Schilling and he just needed to organize it into this useful book.

The film breaks down into a few major sections.

There are three essays on contemporary Japanese cinema totaling about 30

pages – followed by interviews with many prominent directors – Masahiro

Shinoda, Yoji Yamada, Shunji Iwai, Juzo Itami, Takeshi Kitano and Hirokazu

Koreeda to name six of the 15 directors – and this is followed by his reviews

written for the Japan Times from 1989-1999 – around 400 in all. The main

problem of course for most of us is that Schilling caught these in the

theaters and I assume speaks Japanese – most of these are unobtainable

on DVD with English subs. His reviews though are always informative and

well written and can at a minimum be used as a reference for films from

the 90’s and for future DVD releases over here.

Encyclopedia of Japanese Pop Culture, The

By Mark Schilling

Paperback

325 pages

$23

1997

This isn’t specifically a book devoted to film,

but is instead a compendium of various pop cultural happenings over the

past 40-50 years. So it includes a variety of things from celebrities to

music to fads to films and sheds some light on many things I had seen referenced

before but had never quite understood. The book tackles some 67 cultural

pop phenomenons in alphabetical order – often devoting a number of pages

to each. Some of the topics covered are: Doraemon, Instant Ramen, Karaoke,

Pink Lady, Pachinko, Shonen Jump, Tora-san and Ultraman. This is also where

I first came upon Misora Hibari and I am for that quite grateful. Easily

readable, fun and informative.

Eros in Hell

By Jack Hunter and Contributors

Paperback

210 pages

$20

1998

I have to say that I am not a “pinku” fan in particular and am not at all familiar with the genre or the films talked about in this book. Still many Westerners associate Japanese film with many of the extreme themes that “pinku” films immerse themselves in – bondage, rape, S&M and other various fetishes that you won’t come across in your local Blockbuster. The first chapter gives a high level view of the origin of the “pinku” film which begins in the early 1960’s, but really exploded later on in the late 60s’ and early 70’s when the film studio Nikkatsu converted over to almost exclusively producing films of this genre.

Other subjects covered in the ensuing chapters are:

2 .The films of Koji Wakamatsu who was one of the first and most eminent “pinku” directors who mixed sex and political themes – the film “Go, Go Second Time Virgin” may be the most familiar to Westerners.

3. The third chapter focuses on rape and torture films that fall under the term “ero-guro” films.

4. This chapter is devoted entirely to the classic film “In the Realm of the Senses” directed by Nagisa Oshima,

5. The works of director Hisayasu Sato who has been one of the premiere “pinku” directors of the 80’s and 90’s and whose films are a clash of sex, violence and psychosis.

6. Even perhaps more disturbing is the subject matter of this chapter – “Ultraviolence – Sex, Slaughter and Sacrifice” that details films (accompanied by some gruesome photos) of extremely graphic violence as in the “Guinea Pig” series.

7. The seventh chapter consists primarily of an interview with Takao Nakano who has specialized in outrageous trashy films full of nude females, tentacles, female wrestling and so forth.

8. The final chapter veers away from traditional “pinku” films into more recent independent experimental punk films such as those by Sogo Ishii and Shinya Tsukamoto.

Though the material covered in this book may

feel exploitive, the writing is not – it is very measured and informative

and is enlightening about a genre that is for the most part a mystery to

me and in all honestly will with perhaps a few exceptions remain that way.

Somewhat at odds to the serious writing style are the enormous number of

black and white film stills that are in fact quite exploitive for the most

part with reams of naked breasts and bondage being thrown at the reader.

Japanese Cinema

By Thomas Weisser and Yuko Mihara Weisser

Paperback

331 Pages

$20

The film books from Weisser – this one and his book on Hong Kong films – have been smacked around for years and for some fairly good reasons. They basically consist of nothing but 2-3 paragraph reviews of hundreds of films and so one would expect that they would be fairly accurate as the books exist only for this reason. But as has been chronicled by people with much more knowledge than I have, the reviews are often very wrong – just the basic facts and often to such a large degree that one has to assume that Weisser either never watched the films and took his information from elsewhere such as the back of the video box or he watched them years before he wrote the reviews and simply didn’t remember them all that well.

Nevertheless, even with that preface for many

Asian film fans there was practically nowhere else to turn for information

on films pre-internet days and before a flood of other books came out and

his terse pulp descriptions of the films often sent us scurrying off to

find them by hook or by crook. The same can be said about the Japanese

films he covers – there are films he writes about that can be found nowhere

else internet included. The only problem is of course that most of the

films are not available and so you can only dream of someday coming across

them. His bent is for extreme, action and exploitation films and the book

has a number of small black and white photos accompanying the reviews.

Japanese Film: Art and Industry, The

By Joseph Anderson and Donald Ritchie

Paperback

477 pages

$25

1982

“Are movies made in Japan” was a comment made in the United States in the 1950’s to an emissary from the Japanese film industry and this book makes clear that in fact Japan has an enormously rich and diverse film history that goes back to the beginning of the 20th century. For anyone that wants to receive a thorough background in Japanese film history up until the late 1950’s, I can’t imagine a better book than this. This covers trends, themes, directors, studios, film technique and much more in a manner that is scholarly but still fairly digestible. The only issue is that the book throws out so many titles, actors and directors at you in its dense format that it is impossible to retain much more than impressions at a high level the first time through. What it leaves you with though is an incredible desire to learn more about it and to see many of the films referenced – some of them sound fascinating.

The book is relayed in chronological order

beginning with silent film era and the use of the “benshi” – who narrated

the films to the audience – and the slow transition to talkies that led

to the demise of the “benshi” tradition. Following chapters cover the pre-WWII

period describing the creation of the major studios and the advent of a

group of young directors who were to change the face of Japanese films

for decades to come. Two chapters are devoted to the film industry during

the war and then he details how the industry adapted to the post-war conditions

under the censorious eye of the U.S. occupation. Another 100 pages take

up the films of the 50’s. The films referenced tends to focus very much

on the classic directors – Ozu, Mizoguchi, Mikio Naruse, Kurosawa

- as one might expect but there are also loads of films discussed by much

lesser known directors. Sections are also included with biographies of

the prominent directors as well as some of the better known actors - even

including one on Hibari Misora! In truth I was not really ready for this

book due to the paucity of classic films I have seen but I am glad I did

so anyways because it gives me a much higher appreciation of Japanese film

even if the details are still quite fuzzy in my mind.

Monsters are Attacking Tokyo

By Stuart Galbraith

Paperback

191 pages

$17

1998

Many of us had our first contact with Japanese cinema as youngsters sitting around the television watching giant monsters thrash each other or demolish cities though at that age few of us had a clue that the films were coming from some foreign land far far away. As we grew older many of us stopped watching these films as something from our childhood and moved onto to other things, but Galbraith makes a strong case that this uniquely Japanese genre (Kaiju eiga) should be held in higher esteem and not looked down upon as campy laughable escapism. Much of this image by Westerners was derived from the fact that the films we saw were often poorly re-edited and dubbed. At the time of their most prolific period – the 1950’s and 1960’s – these films were in fact as advanced technically as any sci-fi coming out of Hollywood and were very popular in Japan. They were not considered B-films in Japan in the same sense that much of the sci-fi was that came out in Hollywood was during this time and they helped turn around the Japanese film industry after WWII.

I have not been a big fan of these films and

have admittedly seen very few since childhood, but was recently extremely

impressed by the first Godzilla shorn of the dubbing and Raymond Burr.

It took on a completely different persona - it was no longer campy but

was actually a very melancholic film about the state of humanity at the

time. So it is interesting to read a book that takes these films seriously

though this is in no way an academic treatise – but instead a heartfelt

fan valentine to them. The film is broken down into four main sections

– an overview of the genre from the beginning to the date of the book,

an index of the major players in the genre, an assortment of interviews

with many of these and finally short reviews of about 100 films. The only

thing I would have preferred was his organizing the interviews differently

– he breaks them up to address certain aspects of the genre while I think

I would have preferred simply reading the interviews of individuals in

total. There are also lots of images to go along with this. This is an

easy enjoyable introduction to the world of Kaiju Eiga!

New History of Japanese Cinema, A

By Isolde Standish

Hardback

341 pages

$40

2005

The picture (Tange Sazen) on the cover of the book misled me into thinking that this might be a populist foray into the history of Japanese film, but it was far from that. This is a very academic, scholarly and well researched work that details how historical, social and cultural changes in Japan affected the content and themes of films or as Standish writes “an approach that attempts to reach an understanding of the relationship between filmmaking practice, the contexts of the economic and sociopolitical, and their connections to narrative themes in cinema”. She follows this with “In order to avoid a reductionist analysis and in view of the often nonlinear and nondiachronic nature of “history” as it imparts on human experience”. This last sentence gives a perhaps extreme indication that getting through 341 pages might be an arduous task and in truth I gave up for a while, but I later returned to the book with a different mindset and found much of what it relates to be very interesting and that it delves into areas that I had not come across in my other readings on Japanese film.

The book isn’t so much interested in the films

themselves in terms of critical analysis, but instead uses various films

to explore cinematic themes and relating these back to what was taking

place in society. She delves seriously into the pre-WWII growth of nationalism

and how films reflected this, the strict guidelines of WWII censorship

and the explosion after the war of a very humanistic wave of films from

Kurosawa and others that was offset later by the introduction of the Japanese

“New Wave” of Oshima and other young hard edged directors. Though her chronology

of films is quite up to date – “Ichi the Killer” is referenced – the amount

of material written on films after 1990 is fairly limited. For those interested

in a serious slog through Japanese film history, this contains a lot of

useful information and thinking.

Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film

By Chris Desjardins

Paperback

255 pages

$15

2005

As a programmer for the influential American Cinematheque, Chris D. was one of the early voices in the West to espouse and expose Japanese films that fell outside of the typical serious classical works from Ozu and Kurosawa. These films that are primarily from the 1960’s and 1970’s were pure pulp explosions of joy from the genres of the yakuza, samurai and exploitation and were a revelation to many – they just reeked with cool. He displays an astonishing knowledge of these films – most still unavailable in the West – in this book that is a fan friendly love letter to the films he clearly cherishes.

The format of the book is fairly simple – he devotes a separate chapter to those directors that he considers “outlaw” masters – i.e. they broke with convention and by doing so made some of the great films of our time. He also includes two actors who are cult icons. Each chapter is broken into three sections – an overview of their work, a filmography and an interview with them. In the overview many of their films are discussed and the interviews generally are of 5-6 pages in length. The directors covered are:

Kinji Fukasaku

Eiichi Kudo

Junya Sato

Kihachi Okamoto

Kazuo Ikehiro

Masahiro Shinoda

Yasuhara Hasebe

Seijun Suzuki

Teruo Ishii

Koji Wakamatsu

Takashi Miike

Kiyoshi Kurosawa

And the two actors are Sonny Chiba and the fabulous Meiko Kaji.

Both the individual overviews and interviews

are informative and easy to take in and one is constantly impressed by

how deep his knowledge on these films. At times the interviewee is quite

surprised as well that someone from the West knows so much about their

movies. In the appendix he also includes a short essay on female action

films and a short look at the various film studios.

Samurai Film, The

By Alain Silver

Hardcover

236 pages

$24

1983

The samurai film is perhaps Japan’s most unique genre of mainstream film - while giant monsters or Yakuza films have their antecedents in similar western genres the samurai film is closest to the soul of the country. Samurai films go back to silent era and though there have been periods in which it has diminished in popularity they are still being made today and the popularity of the recent films from Yoji Yamada (“Twilight Samurai”, “Hidden Blade”) reconfirm this long lasting affinity with the Japanese audience. Other than simply often being terrific action films and dramas, the Samurai film also imbues itself with themes of honor, sacrifice, obligations, rebellion against the power structure, loyalty to friends, family, clan and country – all themes that resonate well in Japanese society. Characteristics that they perhaps yearn for in the same way that Westerns appealed for such a long time to the urban masses of America. Pre-WW II the samurai films generally were referred to as “jidai-geki” in which the period drama tended to overshadow the action, but beginning in the 1950’s the genre took on a different face – one of questioning authority and loads of action – referred to as “chambara”. It is these latter films that Silver focuses on for this book. This is considered the golden age of the Samurai film – the mid 50’s to the mid 70’s – and numerous classic films were produced.

This book is considered the authority on the Samurai film – it is not a pop exploration of the genre but approached very much from a serious film perspective (Silver has written on various other film genres) with in depth analysis on the genre, directors and specific films. It is highly informative though at least for me at times too analytical – especially of films that I have not yet seen – though I would definitely want to revisit this work after seeing some of these films to see what he had to say. He covers the basics though he spends very little time on the more extreme or cult like samurai films – a short mention of Lone Cub, none of Lady Snowblood for example. Here is what the book does cover.

1. A few chapters to put the films in historical

and cultural context.

2. Akira Kurosawa

3. Dissects three films in chapter 4 – “The

Ambitious”, “Hari-Kiri” and “Rebellion”

4. A terrific chapter that delves into the

series of Zatoichi, Crimson Bat and Son of the Black Mask as well as the

character of Miyamoto Musashi in his various film incarnations.

5. A lengthy welcome chapter (55 pages) on

the films of Hideo Gosha.

6. The final chapter touches on directors

Kihachi Okamoto, Masahiro Shinoda and the decline of the samurai film towards

the end of the 70’s.

7. There is also a glossary of terms and filmographies

of directors with cast information.

Stray Dogs and Lone Wolves – The Samurai Film

Handbook

By Patrick Galloway

Paperback

234 pages

$20

2005

The author approaches his subject very much from the perspective of a fervent fan of the genre as opposed to an academic analysis. He makes this clear in his introduction when he states first that he just feels the genre hasn’t been covered sufficiently in English and that writing the book saved his marriage! Of course, it may do damage to your relationship because reading his book will likely lead you to wanting to watch more samurai books than your significant other will want to put up with. For those already well versed in the subject there may not be a lot new here, but Galloway’s writing is fairly entertaining and his film reviews are enthusiastically rendered.

The first four chapters are basic background

material – he puts the samurai film into historical context, gives a high

level overview of the genre and the film companies that were behind them

and has some biographical information on the major directors and stars.

He follows this with 51 two to three page reviews that are in chronological

order beginning with Rashomon in 1950. The reviews are well-written

and easy reading and have a certain dramatic tension to them as he relates

the major plot points. He also often includes some additional information

on the production, some of the character actors and so on. One really strong

point for me is his actor identification of all the characters. The films

covered are the major ones – but he gives equal time to the serious classics

and to the pulp classics. His selection criteria appears to be films that

are readily available and so unfortunately (and really the only weakness

of this book) he doesn’t cover any films that are somewhat obscure. So

for any one with an interest in knowing more about the samurai film, this

is a terrific place to start.

TokyoScope – The Japanese Cult Film Companion

By Patrick Macias

Paperback

235 pages

$20

2001

Over the past couple of years there has been a sudden surge of interest in Japanese films with the publication of books on samurai, Miike, horror and the yakuza along with the release of a number of older films on DVD in the West. But Macias was perhaps the first to tackle a wide range of films in English that fell outside of the usual study of Japanese film – i.e. Kurosawa, Ozu and such. He terms them “cult” films and I would perhaps disagree with that because many of these films were not considered cult films in Japan and were indeed mainstream fare but it is perhaps an easy manner to categorize the films he discusses.

The book is broken down by various genres/directors

in which he first gives a short introduction and then follows this with

a number of reviews (usually 8-10) of films pertaining to that genre. He

also mentions if the films are available, but since this was put out before

the recent explosion of Asian films distributed by the West on DVD it is

somewhat out of date. These genres are: Giant Monsters (Kaiju Eiga), Sonny

Chiba (a genre of a sorts), Horror, Yakuza, Kinji Fukasaku, Banned (5 Forbidden

Films), Pink and Violence, Panic and Disaster and he finishes with a chapter

on Miike. Within these he often has sidebar interviews with important contributors

to the genre or informational essays on subjects such as bios on Hiroyuki

Sanada, Etsuko Shihomi, Bunta Sugawara and Tetsuro Tanba among others.

The book is very much fan-based – clearly an ode to the films he loves

or thinks are cool. This is by no means an in depth examination of any

of these genres – it instead serves as a nicely packaged book to whet your

appetite and send you off looking for more.

Yakuza Movie Handbook, The

By Mark Schilling

Paperback

335 pages

$20

2003

As in all of his writing on Japanese film, Schilling produces a very informative and enjoyable read here as he delves into the world of the Yakuza film. His vast breadth of knowledge on Japanese film, history and culture is impressive and he brings this to the book. Being a respected reviewer for the Japan Times also allows him access to many of the important personalities within the industry and this results here in some great interviews. The book covers most of what anyone would want to know about the Yakuza films – at least from the perspective of someone like myself who is new to all of this.

Here is what the book contains:

1. A 21 page overview of the history of the

Yakuza film.

2. A number of profiles and sometimes interviews

with many of the prominent directors such as Kinji Fukasaku, Teruo Ishii,

Tai Kato, Kitano, Miike and Suzuki.

3. The same format is continued with actors

who starred in these films – Noboru Ando, Junko Fuji, Akira Kobayashi,

Jo Shisido, Bunta Sugawara, Ken Takakura, Koji Tsuruta and others.

4. The final section contains about 120 film

reviews that are broken into a summary of the film followed by a critique

of it – generally 4-5 paragraphs in total. Of course most of these films

are not available with English subtitles and so reading these reviews and

not having an opportunity to watch them can be more frustrating than rewarding

– but with the recent western releases of many older Japanese films hopefully

some of these will see the light of day.

One of my favorite recent discoveries in Japanese film is the actress/singer Hibari Misora. She sings in all of her films and can charm you within an inch of your life. I picked up a 5 disc cd of her music which is wonderful and bought this hardcover book from cdjapan I believe. It is filled with hundreds of pictures of her from childhood to her death and many obviously from her films. It is 250 pages and cost about $50.