Park Chan-wook’s third and final piece in his trilogy of revenge films is so visually glorious and imaginative that one can easily be swept along like a swift rip tide. He seems to constantly play with his presentation – imagery that made me gulp like a school boy in love – an ever constant parade of changing colors, texture and camera angles with playful swirls and doodles as add-ons. It simply knocks you out and makes you wonder why all directors can’t take the time and care that he must have. Yet this isn’t quite enough to allow you to completely overlook the lack of a strong emotional core within this beautifully wrapped gift. What is this film trying to say to us – what emotions are Park trying to pull out of us? I am not sure, but I felt little beyond the total cool factor of many of the shots and the striking demeanor of the lead actress.

My rating for this film: 8.0

Reviewed: 01/06

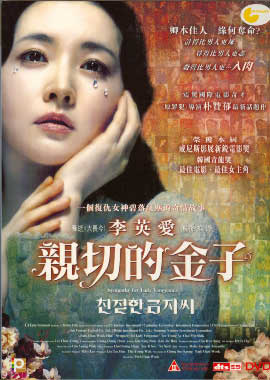

Director Park Chan-Wook. Who is this man? Viewing his movies is a window to a mind of a genius who amalgamates literary motifs, film traditions, taboos, visual arts, and philosophical themes in originality and boldness that has been unrivalled for a long time. Lee Young Ae’s poster easily evokes the Catholic fanaticism and surrealism of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Santa Sangre. It is a laborious study in itself just to identify and understand the roots, inspirations, and cultural influences that SFLV has incorporated: a patchwork of Park’s erudition. SFLV is the third installment of Park’s cinematic trilogy of revenge tales, but SFLV is unique in that the central character is a woman who is intent on redemption, going beyond the old formula of cat-and-mouse vengeance.

SFLV is a mockery of institutionalized religion. Our heroine Geumja (Lee Young Ae) uses religion, its propaganda, and the influence of its followers for her ulterior motives. Although she is an iconoclast in the end, she does pick up and is obsessed with one of the essential tenets of Christianity – atonement. I laughed out loud when the Church representative pleads with Geumja, “Please go back to Church!” It reminds me and so many hapless victims of the times when these Church “cults” in the guise of legitimate religion knock on our doors, invade our space, and attempt to convert us. Geumja’s reaction deserves a few cheers. She replied “I converted to Buddhism!” (I hear it’s quite effective to get rid of these people) to the Church imbecile’s aggravation. He wasn’t so much an imbecile as we’ll see, and his future actions against Geumja are another testament to SFLV’s distaste towards these coercive religious organizations. SFLV is all about unorthodoxy.

SFLV is a women’s prison story and is there ever a women’s prison story that is lacking in sexual deviances? Park’s movies have a tendency to showcase sexual situations that are highly uncomfortable to watch, and SFLV’s sexual discomfort is better watched when dinner is long consumed. SFLV’s prison is more like an after school playhouse with pink walls, further accentuating the surreal visuals that are so haunting in contrast to the barbarism of prison life. Geumja comes out of prison and meets her former prison mate friends, all of whom she has helped at great lengths to secure their loyalty and garner their help for her vengeance scheme.

One of Geumja’s friends is a Bonnie type with her husband who is Clyde. I suppose this criminal husband-and-wife set of characters is a reference to some comic strip or animation but it’s only a guess. They offer one of the few good laughs in SFLV. Geumja’s friend bemoans on being separated from her beloved during her sentence, “Why can’t there be prisons for couples?” Her husband replies, “It won’t be jail. It will be paradise.” Ever so in love they kiss and Geumja reacts with a frozen, disgusted gaze.

Yes, Geumja, a Korean Lady MacBeth, uses people for her ulterior motives. She is damn scary. She fantasizes about shooting a man into a bloody mess and wallows in hearty laughter afterwards. She goes so far as to feign love for a lesbian who helps her set up a new life after her release. So how do we end up having any sympathy for Lady Vengeance?

At this point the film enters an unexpected transition that truly moved me and I was awakened from my descent into boredom. The first half of SFLV is perhaps about Geumja’s vengeance plan and tracking down her enemy. There are some revelations in the second half of the story that increasingly shift the audience’s support for Geumja to the fullest but I won’t get into those.

It is how Geumja chose how to conduct her revenge that touched me. As brilliant and incomparable as Choi Min-sik is, he is virtually camouflaged in this role as Mr. Baek, Geumja’s arch-enemy. He is despicable and sick and Choi Min-sik never has a problem portraying unsavory characters. Even though I have a soft spot for Choi Min-sik because he is one of the finest actors in the world, Mr. Baek can easily be played by anyone else, however. There’s no depth or range to his character, but there was plenty in Geumja. Lee Young Ae’s performance is the definition of masterful – she was cruel and calculating, maternal and loving, repentant and guilt-ridden, elegant and sexy, and everything the role called for.

Korean soaps as well as films have a penchant for maximizing the austerity and the sense of noble suffering of Classical scores. In the scene where Geumja congregates the parents of Baek’s victims, the musical score was the most poignant to the point I was in tears. The unmitigated cries of the parents, the children’s pleading for their lives, and the consequent irrevocability of their lives were so dramatically synchronized with the music that my IPOD has been playing mostly Classical for a while now.

Geumja unites her urge for revenge with others’ urge for revenge, a communal act. Reiterating the general unorthodoxy of SFLV, the community rejects the legal system in administering justice. The community of victims takes it upon itself to serve justice, and this is where Geumja shines. She knows her vengeance is not merely personal but communal and gives other victims the opportunity to wreak a bloodbath. The mob often leads itself to chaos without an effective leader, and Geumja takes the lead by saying that she has also killed in prison and puts the increasingly dissenting mob into place. The ethics of this choice of personally taking up revenge instead of surrendering the decision to another power is controversial in moral debate, but this is where Park and his writing team have taken command: you will most likely root for their choice or at least sympathize with it.

Unlike the rationalism and lack of emotion of the legal system towards the search for justice, SFLV pours its outrage without restraint. Human beings are hurt at every level – emotional, spiritual, physical, and psychological, and they would react like animals. Forget the sugarcoating mumbo-jumbo of forgiveness and the hope that the criminal will repent. The victims wrought revenge like animals and this is where the choice feels real and I was moved by SFLV’s courage and honesty. Towards the end of this chapter Geumja brings a cake to celebrate the community’s revenge and/or to mourn the losses that led to this need for revenge. It was one of the most poignant, gut-wrenching moments in cinema – it was done in such a way that I could actually feel the children having become angels who desperately want to comfort their parents and tell them to move on with their lives.

Because the storyline was officially over and SFLV persisted for quite some time rather aimlessly, SFLV somewhat deteriorated towards the end. The end was mostly a symbolic visualization of Geumja’s sense of redemption or lack thereof. At her daughter’s insistence that she is worthy of a life without feeling like a sinner, Geumja ritually (it will be shown in the movie) cleanses herself without really knowing whether she has achieved it or not. She will probably need some time to adjust to her new self as her mission is accomplished. Unfortunately, SFLV still needs room to convince that redemption is as exciting as vengeance.

Rating: 8.0

Three Extremes: Cut – part of a trilogy (2004)

Old Boy (2003)

Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002)

JSA (2000)

Trio (1997)

The Moon is What the Sun Dreams of (1992)