I very much enjoy Nobuo

Nakagawa's horror films from the 1950's in such outings as The Ghost of Yotsuya,

Black Cat Mansion, The Woman Vampire and The Ghost of Kasane. I have yet

to see his most acclaimed film and the one that many years after he directed

it introduced him to a Western audience when it was released on DVD - Jigoku

from 1960. For these films and others not so easily accessed he was given

the title as the Godfather of Japanese Horror. That seems odd that this did

not come about until the late 1950's in that horror films had been a large

part of Western cinema since the silent days and Japanese films had been

clearly influenced by Western films. Also, horror in tales and literature

had been around in Japan for hundreds of years with an emphasis on the supernatural.

Lafcadio Hearn who lived in Japan in the 19th century collected these tales

and put them in a book.

These early films of Nakagawa though often set in modern times have their

roots in these folktales. He was at the studio Shin Toho which beginning in

1956 had moved into non-traditional genres such as thrillers, crime and horror

and this allowed him to make these films. Before he began making horror films,

Nakagawa had been directing films for two decades that were of every sort

of genre but not horror. He found his fame in horror. To today's audience

these films are not particularly frightening - the horror genre has moved

on to more graphic depictions and more sophisticated special effects though

Japanese films like The Ring or The Grudge clearly can be traced back to the

sorts of films that Nakagawa made. These early films shot in black and white

mainly feel atmospheric and spooky with a few jump scares and great imagery.

Generally they feature female ghosts wronged coming back for revenge and

images of them on the ceiling or rising out of the water are quite effective.

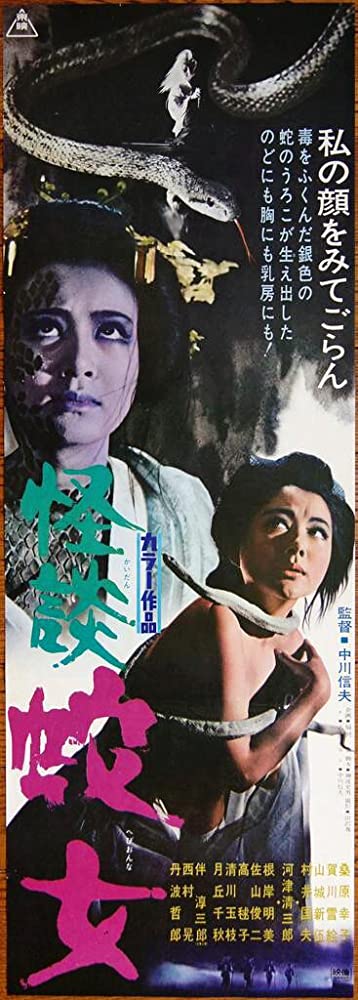

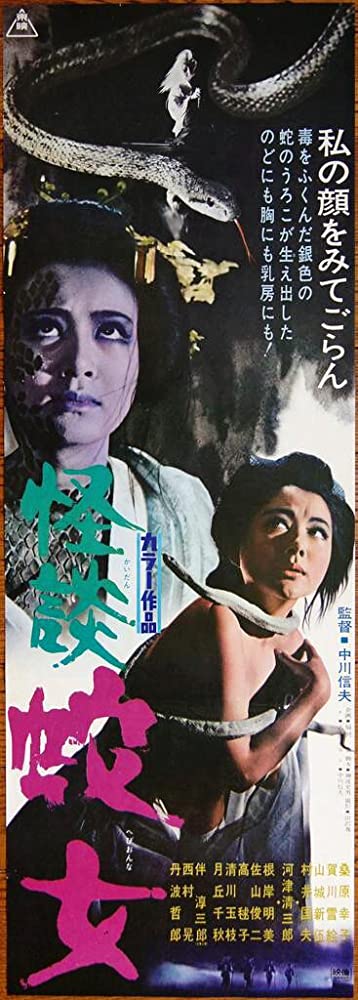

Snake Woman's Curse was made in 1968 after Nakagawa had left Shin Toho for

Toei and had also left the horror genre behind until he returned to it with

this film. To me it felt a bit of a rehash of horror techniques that he had

already made use of in his 1950 films - but this one is shot in bright colors.

Which lessened the horror to me - the spooky atmosphere and scares were not

there as much as he tried by having three angry ghosts looking for justice

and popping up at the most inopportune times - such as during sex. It as really

more of a social drama about exploitation than a ghost story. The ghosts

are almost symbols for the oppressed workers getting back at their capitalist/feudal

overseers. As in the United States, social upheaval was taking place in Japan

during this time with student demonstrations and an active Communist party.

Possibly this influenced his subject choice though he places the story at

the beginning of the Meiji era (1868 - 1912) in a small isolated part of

the country were the majority of the people are tenant farmers scrapping

by on a small piece of land.

A cruel landlord with a crueler wife and a rapist son rule over their tenants

with an iron unyielding hand. When Yasuke (Ko Nishimura) is unable to pay

back his debts he dies begging the landlord with his last words "I will eat

dirt to pay you back". His wife (Chiaki Tsukioka) and attractive daughter

(Yukiko Kuwahara) are forced to go work at the landlord's house under terrible

conditions and the wrathful eye of the wife (Akemi Negishi, who is great here

with her sneers - and who was discovered by of all people Josef von Sternberg

when he was looking for a seductress for his film Anatahan - which I have

never heard of).

Things quickly go bad - the mother is beaten, the daughter raped and after

they die their ghosts come back - sometimes in the form of snakes, some times

only with scaly skin and scare the odious threesome out of their minds. It

takes a long time to get there though with the melodrama taking up most of

the film. What I actually enjoyed more were the scenes of average life - the

weavers singing while they work, the small festivities, the women laughing

among themselves. But the horror element felt too subservient to the

social injustice that Nakagawa seemed intent on.