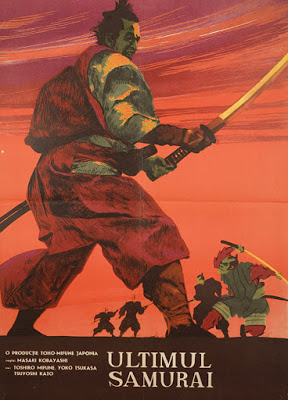

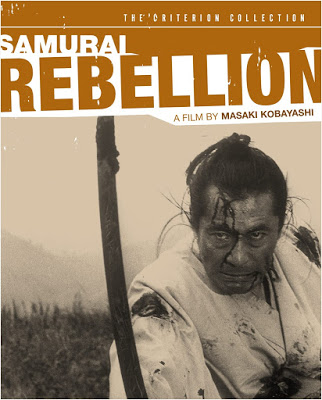

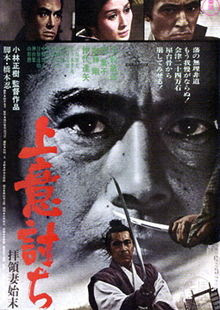

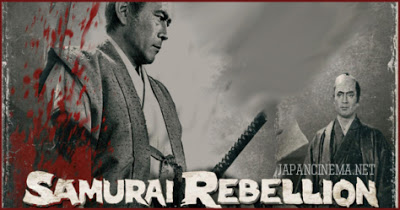

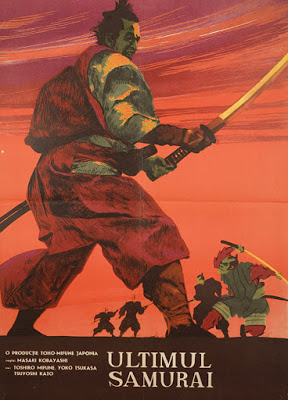

Samurai Rebellion

Year: 1967

Director: Masaki Kobayashi

Rating: 9.0

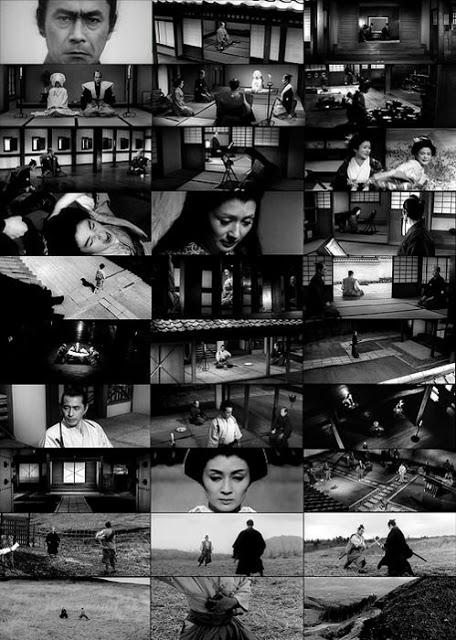

Every now

and then you find yourself in the company of greatness. That is how I felt

while watching this film. Absolutely masterful. I had randomly picked it

out to watch because of its title which implied a good rousing samurai film

full of action and intrigue. About twenty minutes into it I thought who the

hell directed this movie – it is brilliant and yet not at all what I expected.

Ah, it’s Masaki Kobayashi. What I know of his work could fit into a small

thimble but I know that he was considered one the giants of Japanese films

during the 1950’s and 60’s with The Human Condition trilogy which was really

one film broken into three segments totaling ten hours. I have never had

the courage to approach it. He only directed 22 films in his life – he was

often out of step with both the public and the film companies – and of those

only two were period samurai films – both considered classics – this one

and Harakiri in 1963. He also directed the highly regarded ghost story Kwaidan

in his first color film.