III. Ideology and

Spectatorship

Patriarchal Readings

A major concern of feminist film criticism

is that many seemingly progressive filmic views of women, on closer examination,

eventually re-inscribe their role into the dominant patriarchal order.

In action film contexts such recuperation of roles may take several forms.

In the first, the authority wielded by women may itself be delegated, circumscribed

by and answerable to patriarchal power structures. Examples include

police dramas such as the “In The Line of Duty” series of HK cinema, or

titles such as “Fox Hunter” (1995). Secondly, while organized criminal

enterprises may be inherited from the men who founded or ran them (e.g.,

“Widow Warriors,” “Queen’s High”), the new female leaders do not thereby

establish a matriarchy. There is a sense of impermanence about power

wielded in this manner. Third, romance (or romantic overtures) with

a conventional male figure may either establish the woman as having been

desired/possessed in relationships as a back story (“Soul,” “Widow Warriors,”

“She Shoots Straight”), affirm a stereotypic role for a female professional

as object of desire (“Royal Warriors,” 1986; “Forbidden Arsenal,” 1991),

seemingly undo the validity of lesbian or bisexual commitment in a film’s

closing moments (e.g., “Portland Street Blues,” 1998; “The Love That Is

Wrong,” 1993; “City of Desire,” 2001), or temporarily rehabilitate an assassin

(e.g., “On the Run,” 1988; “Her Name is Cat,” 1998; “Black Cat,” 1991;

“Beyond Hypothermia,” 1996).

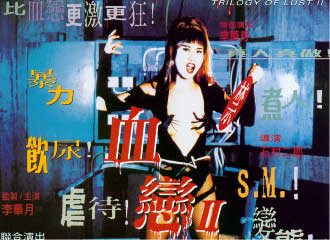

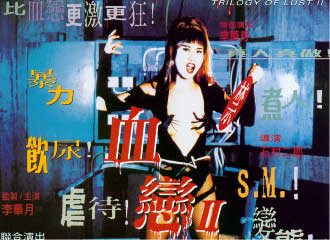

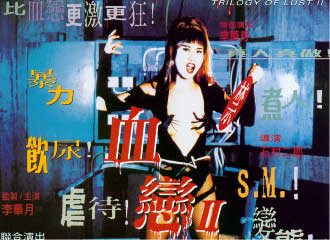

Egregious conduct by female protagonists that

might otherwise be truly subversive (e.g., “Trilogy of Lust II,” 1995;

“Daughter of Darkness,” 1993) may be attributed to childhood abuse by men

as the causal agent. Vengeance films (“Vengeance is Mine,” 1988;

“Her Vengeance,” 1988) are linked to more proximal assaults by men, while

others (e.g., “Red to Kill,” 1994; “Love to Kill,” 1993; “Bet on Fire,”

1988) reflect acute struggles for physical survival. However, all

locate the origins of causality in the behavior of males. Despite

the negative portrayals of male behavior, patriarchal power remains largely

unchallenged.

Egregious conduct by female protagonists that

might otherwise be truly subversive (e.g., “Trilogy of Lust II,” 1995;

“Daughter of Darkness,” 1993) may be attributed to childhood abuse by men

as the causal agent. Vengeance films (“Vengeance is Mine,” 1988;

“Her Vengeance,” 1988) are linked to more proximal assaults by men, while

others (e.g., “Red to Kill,” 1994; “Love to Kill,” 1993; “Bet on Fire,”

1988) reflect acute struggles for physical survival. However, all

locate the origins of causality in the behavior of males. Despite

the negative portrayals of male behavior, patriarchal power remains largely

unchallenged.

Examples of film plots in which women act autonomously,

without apparent reference to patriarchal pressures are quite rare, perhaps

largely due to the traditional coding of the action genre as male.

Examples may be relatively obscure or require oppositional readings.

Yukari Oshima’s character “Madam Yeung” in “Angel” (1987) was beholden

to no one, and exulted in wielding absolute power – irrespective of the

forces ranged against her. It is significant that she was finally

killed by a shot fired by a male police detective. This is the final

form of recuperation – re-imposition of the patriarchal order by arrest

or death.

Examples of film plots in which women act autonomously,

without apparent reference to patriarchal pressures are quite rare, perhaps

largely due to the traditional coding of the action genre as male.

Examples may be relatively obscure or require oppositional readings.

Yukari Oshima’s character “Madam Yeung” in “Angel” (1987) was beholden

to no one, and exulted in wielding absolute power – irrespective of the

forces ranged against her. It is significant that she was finally

killed by a shot fired by a male police detective. This is the final

form of recuperation – re-imposition of the patriarchal order by arrest

or death.

Many HK GWG films navigate between these extremes.

Some do so in ways that both illustrate and subvert the patriarchal order.

An excellent example is provided by “Nude Fear” (1998) in which Kathy Chow’s

brilliant, professionally driven homicide inspector resists sexual harassment

on the job, but nonetheless engages in occasional affairs with married

men – one of which proves nearly fatal.

Many HK GWG films navigate between these extremes.

Some do so in ways that both illustrate and subvert the patriarchal order.

An excellent example is provided by “Nude Fear” (1998) in which Kathy Chow’s

brilliant, professionally driven homicide inspector resists sexual harassment

on the job, but nonetheless engages in occasional affairs with married

men – one of which proves nearly fatal.

A bare handful of films do not privilege male

agency in some form. One rare exception is “Night Caller” (1985)

in which rejection by a lesbian partner prompts Pauline Wong’s character

to initiate a homicidal spree. A female detective (Pat Ha) is instrumental

in both freeing her male colleague and stopping the killer. The lurid

and extreme nature of the narrative suggests the distance to be traversed

before finally outrunning patriarchal agency.

A bare handful of films do not privilege male

agency in some form. One rare exception is “Night Caller” (1985)

in which rejection by a lesbian partner prompts Pauline Wong’s character

to initiate a homicidal spree. A female detective (Pat Ha) is instrumental

in both freeing her male colleague and stopping the killer. The lurid

and extreme nature of the narrative suggests the distance to be traversed

before finally outrunning patriarchal agency.