(photo by Quang-Tuan Luong/terragalleria.com)

“Hong Kong has always been a very special city. Its international style is influenced by the east and west.” (Josie Ho, “Horror Hotline...Big Head Monster”)

Intercultural Entertainment

Intercultural Entertainment

Hong Kong genre films enjoy enduring popularity with diverse audiences, as evidenced by the fact that retail editions of many titles produced since the mid-1980s have remained in print. Developments in digital media and Internet retailing also contribute to the distribution of an increasingly “intercultural” (Note 1) entertainment form, serving not only the home markets of South China, neighboring Asian states and globally dispersed Chinese-speaking populations, but increasingly also a sub-culture of non-Asian consumers. Serendipity has also played a part. Pre-1997 British administrative regulations imposed relatively uniform requirements for English subtitling on HK cinematic products, rendering them accessible to English-speaking viewers. Additionally, the 1997 transfer of administrative responsibility for HK to China precipitated an appreciable migration of industry talent – especially to the United States – bringing auteurs and actors to the attention of new audiences.

1. See Susan Napier’s discussion of anime and

global cultural identity for a consideration of borrowing of popular culture

texts. Susan Napier, Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke:

Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. New York: Palgrave,

2001, pp. 22 – 27.

2. David Bordwell, Planet Hong Kong:

Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. Cambridge: Harvard

University Press, 2000, pp. 161 – 170, pp. 210 – 217.

3. Bordwell, op. cit., pp. 191 – 196.

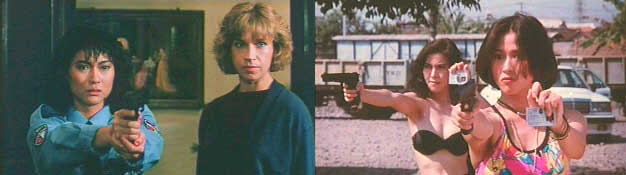

4. Bordwell, op. cit., pp. 156 – 160.

5. See Bordwell, op. cit., pp. 194 – 196 for

a discussion of revenge plots.

6. For a discussion of postmodernism in HK

cinema, see Stephen Tao, Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions.

London: British Film Institute, 1997, pp. 243 – 255.

7. Bordwell, op. cit.

8. Frederic Dannen & Barry Long, Hong

Kong Babylon: An Insider’s Guide to the Hollywood of the East.

New York: Miramax, 1997.

9. Lisa Oldham Stokes & Michael Hoover,

City on Fire: Hong Kong Cinema. London: Verso, 1999.

10. Rick Baker & Toby Russell, The Essential

Guide to Hong Kong Movies. London: Eastern Heroes, 1994.

Thomas Weisser, Asian Cult Cinema. New York: Boulevard Books,

1997. Paul Fonoroff, At the Hong Kong Movies: 600 Reviews from

1988 till the Handover. Hong Kong: Film Biweekly Publishing

House, 1998. John Charles, The Hong Kong Filmography, 1977 – 1997:

A Complete Reference to 1,100 Films Produced by British Hong Kong Studios.

Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, 2000.

11. Bey Logan, Hong Kong Action Cinema. Woodstock:

The Overlook Press, 1996. Stefan Hammond & Mike Williams, Sex

and Zen and a Bullet in the Head: The Essential Guide to Hong Kong’s

Mind-Bending Films. New York: Fireside, 1996.

Stefan Hammond, Hollywood East: Hong Kong Movies and the People Who

Make Them. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 2000.

12. See Bordwell, op. cit., pp. 149 – 156

for a discussion of genre in HK films and, for a broader overview of genre,

Jane Feuer, “Genre study and television.” In, Robert Allen (Ed.),

Channels of Discourse, Reassembled. London: Routledge, 1992,

pp. 138 - 160.

13. Bordwell, op. cit., pp. 19 – 25 argues

that the HK film “Gun Men” (1988) was directly inspired by De Palma’s “The

Untouchables.” “First Shot” (1993) is another HK film reportedly

modeled on this title (Weisser, op. cit., p. 75).

14. According to Weisser, op. cit., p. 51,

“Deadly Angels” (1984) was the first of a style of HK contemporary female

action films that has since been referred to as “Girls With Guns” (GWG)

in English language fan writing. A similar case could be made for

“Girl with a Gun” (1984) that appears directly inspired by the American

revenge film “Ms. 45.” Accordingly, the fusion of camp with viciousness

that that seems to define GWG might plausibly be traced to “Charlie’s Angels”

and “Ms. 45,” respectively. The principal performers in GWG films

and their associated filmographies are reviewed in Rick Baker & Toby

Russell, The Essential Guide to Deadly China Dolls. London:

Eastern Heroes, 1996.

15. See Wendy Arons, “If her stunning beauty

doesn’t bring you to your knees, her deadly drop kick will.” In,

Martha McCaughey & Neal King (Eds.), Reel Knockouts: Violent

Women in the Movies. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001,

pp. 27 – 51.

16. For an overview of narrative theory, see

Sarah Kozloff, “Narrative theory and television.” In, Allen, op.

cit., pp. 67 – 100.