1985 - 1988

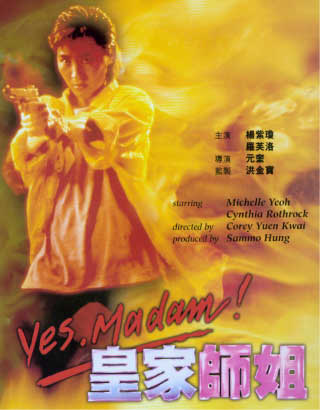

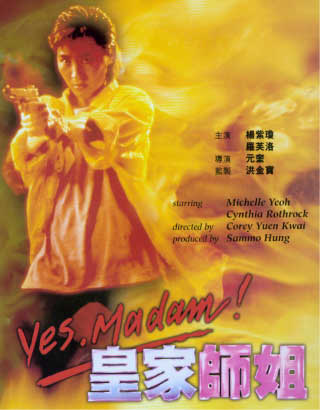

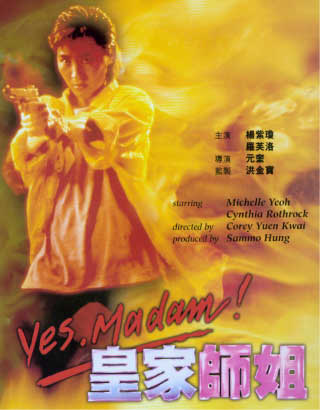

“Yes, Madam” (1985)

(D & B Films Co.; Dir. Corey Yuen Kwai)

“Yes Madam” merits a place on any shortlist

of HK action movies due to its influence on the genre. Although Michelle

Yeoh would only fully develop her combative police detective persona in

“Royal Warriors,” “Yes, Madam” was a worthy beginning. Reportedly

resulting from a suggestion by Sammo Hung, the film appears to represent

a calculated compromise. The hard edge of action is softened by an

extensive comedy sub-plot associated with a trio of petty criminals who

inadvertently steal an incriminating piece of microfilm. Dick Wei

plays the principal thug sent to retrieve it.

Despite a fairly pedestrian plot, the film nevertheless

feature some very fine action choreography, with exciting performances

by Michelle Yeoh and Cynthia Rothrock as police detectives investigating

the murder of a visiting British police officer. Yeoh provides one

of her best appearances, while Rothrock’s martial arts skills are particularly

impressive here. Their screen partnership is quite effective – with

sufficient abrasiveness to sustain interest.

Despite a fairly pedestrian plot, the film nevertheless

feature some very fine action choreography, with exciting performances

by Michelle Yeoh and Cynthia Rothrock as police detectives investigating

the murder of a visiting British police officer. Yeoh provides one

of her best appearances, while Rothrock’s martial arts skills are particularly

impressive here. Their screen partnership is quite effective – with

sufficient abrasiveness to sustain interest.

Two of the set-piece action sequences – Yeoh’s

single-handed demolition of a gang of bank robbers, and the extraordinary

stunt work during the extended final fight – are among the classics of

HK action cinema. In between, Yeoh as “Inspector Ng” and Rothrock

as “Inspector Morris” repeatedly clash over police methods, but eventually

close in on the petty thieves and the counterfeiting ring in the background.

In the tradition of many police action films they eventually shed their

badges to seek final justice outside the constraints of the law.

Two of the set-piece action sequences – Yeoh’s

single-handed demolition of a gang of bank robbers, and the extraordinary

stunt work during the extended final fight – are among the classics of

HK action cinema. In between, Yeoh as “Inspector Ng” and Rothrock

as “Inspector Morris” repeatedly clash over police methods, but eventually

close in on the petty thieves and the counterfeiting ring in the background.

In the tradition of many police action films they eventually shed their

badges to seek final justice outside the constraints of the law.

“Royal Warriors” (1986)

(D & B Films Co.; Dir. David Chung Chi-man)

Featuring perhaps Michelle Yeoh’s best contemporary

action role, “Royal Warriors” essentially defined recent HK policewoman

genre films. Yeoh’s physical agility and mastery of action choreography

are on display, and her final fight against a murderous, vengeance-seeking

veteran wielding a chainsaw is electrifying. The talc flies as the

kicks connect. Henry Sanada provides strong dramatic support as a

Japanese detective stranded in HK.

The plot involves “Michelle Yip” (Yeoh) and her

police colleagues thwarting an airline hijacking. Identified as heroes

by the news media, they become the targets of vengeance by a group of military

veterans responsible for the failed hijack. The gang then proceeds

to attack the police officers as individuals, resulting in the death of

relatives and colleagues.

The plot involves “Michelle Yip” (Yeoh) and her

police colleagues thwarting an airline hijacking. Identified as heroes

by the news media, they become the targets of vengeance by a group of military

veterans responsible for the failed hijack. The gang then proceeds

to attack the police officers as individuals, resulting in the death of

relatives and colleagues.

As Yip races to solve the case, she is required

to sidestep unwanted romantic overtures as well as shoot it out with the

gang. Car chases, stunt falls and the final fight are all very well

executed, although the gunplay is not. Other films have treated individual

elements in a more spectacular fashion, but “Royal Warriors” remains an

engaging and influential genre title. Some reviewers have speculated

about influences on action film beyond the confines of the HK industry.

As Yip races to solve the case, she is required

to sidestep unwanted romantic overtures as well as shoot it out with the

gang. Car chases, stunt falls and the final fight are all very well

executed, although the gunplay is not. Other films have treated individual

elements in a more spectacular fashion, but “Royal Warriors” remains an

engaging and influential genre title. Some reviewers have speculated

about influences on action film beyond the confines of the HK industry.

“Angel” (1987)

(Molesworth; Dirs. Raymond Leung Pan-hei, Tony

Leung Siu-hung, Ivan Lai Kai-ming)

The surprise hit “Angel” can truly be described

as the progenitor of “Girls With Guns,” and rapidly spawned two direct

sequels. Three relative unknowns – Moon Lee, Elaine Lui and Yukari

Oshima were propelled to prominence in action films by their performances

that for one of the first times cast women in the leading roles as both

heroes and villain. “Angel” was also unusual in that it received

relatively widespread distribution in the European market.

Superficially, the plot bore resemblances to the

“Charlie’s Angels” concept of female undercover crime fighters assigned

to solve especially challenging cases. In “Angel,” Moon Lee and Elaine

Lui would be teamed with Hideki Saijo and Alex Fong. However, the

film departed from formula in several significant ways. For one thing,

the combat is at close quarters with no holds barred. Point-blank

shootings and indifference to the suffering of enemies (one man is used

as a shield for a grenade detonation) helped re-define screen combat roles

for female performers. The other major distinguishing feature is

Yukari Oshima’s “Madam Yeung.” Seemingly emerging from nowhere, Oshima’s

performance is riveting. Although much of her screen time is abruptly

edited, she dominates all her scenes. As the boss of a ruthless drug

cartel, Yeung not only expresses absolute power but also exults in instilling

fear in those around her. Yeung is a sadist who can dress and act

like a normal person, but keeps a private dungeon. The editing only

yields a glimpse of the horrors, but it’s sufficient.

Superficially, the plot bore resemblances to the

“Charlie’s Angels” concept of female undercover crime fighters assigned

to solve especially challenging cases. In “Angel,” Moon Lee and Elaine

Lui would be teamed with Hideki Saijo and Alex Fong. However, the

film departed from formula in several significant ways. For one thing,

the combat is at close quarters with no holds barred. Point-blank

shootings and indifference to the suffering of enemies (one man is used

as a shield for a grenade detonation) helped re-define screen combat roles

for female performers. The other major distinguishing feature is

Yukari Oshima’s “Madam Yeung.” Seemingly emerging from nowhere, Oshima’s

performance is riveting. Although much of her screen time is abruptly

edited, she dominates all her scenes. As the boss of a ruthless drug

cartel, Yeung not only expresses absolute power but also exults in instilling

fear in those around her. Yeung is a sadist who can dress and act

like a normal person, but keeps a private dungeon. The editing only

yields a glimpse of the horrors, but it’s sufficient.

Some of the cinematography is inspired.

As the camera pans from decorative marionettes to Yeung, the symbolism

of control of captive beings is wordlessly evoked. At another point

the camera looks up into her face as she pins down and mocks Alex Fong.

Here, the camera’s viewpoint is almost the eye of the victim. Oshima’s

uncanny physical flexibility allows her to bring her body into positions

of disturbing, controlling intimacy. She is, quite simply, hypnotic

in a relatively small part. A measure of her screen presence is her

ability to exude menace while wearing a bathing suit or simply sitting

eating a solitary meal.

Some of the cinematography is inspired.

As the camera pans from decorative marionettes to Yeung, the symbolism

of control of captive beings is wordlessly evoked. At another point

the camera looks up into her face as she pins down and mocks Alex Fong.

Here, the camera’s viewpoint is almost the eye of the victim. Oshima’s

uncanny physical flexibility allows her to bring her body into positions

of disturbing, controlling intimacy. She is, quite simply, hypnotic

in a relatively small part. A measure of her screen presence is her

ability to exude menace while wearing a bathing suit or simply sitting

eating a solitary meal.

When Yeung’s poppy fields are torched by a law

enforcement task force, she retaliates by ordering police officials assassinated.

The Angels break into Yeung’s corporate offices, eventually tracing her

headquarters. After Alex Fong’s character is captured and held by

Yeung, the Angels mount an assault to rescue him. A complex sub-plot

involving an armored car bullion robbery eventually leads the Angels to

a final showdown with Yeung and her men.

When Yeung’s poppy fields are torched by a law

enforcement task force, she retaliates by ordering police officials assassinated.

The Angels break into Yeung’s corporate offices, eventually tracing her

headquarters. After Alex Fong’s character is captured and held by

Yeung, the Angels mount an assault to rescue him. A complex sub-plot

involving an armored car bullion robbery eventually leads the Angels to

a final showdown with Yeung and her men.

“Angel” may not boast the best production values,

but has certainly endured as a cult classic. High quality prints

are difficult to locate, but are worth the effort.

“Her Vengeance” (1988)

(Dir. Lan Nai-tai)

The acting talent of Pauline Wong and Lam Ching-ying

elevate this straightforward vengeance plot into something unique.

While the action certainly merits attention, it’s the acting and characterization

that distinguish the film. Wong plays an unassuming nightclub employee

in Macao who alienates a gang of drunken men (led by Shing Fui-on).

They tail her after her shift, and mount a gang assault. This is

depicted without gratuitous elements – unlike some of the relatively graphic

violence that follows later. In this sense the film serves as an

antidote to other titles that may linger on such assaults but dispense

perfunctory justice.

Wong’s character portrays both suffering and resilience.

She attempts to enlist the aid of her former brother-in-law (Lam) – an

ex-triad now confined to a wheelchair. A lounge owner in HK, he hires

her as a waiter and finds her a place to live, but refuses to help in her

quest for vengeance. She, however, has other ideas. When a

chance encounter provides access to the first assailant (Shing), she improvises

the first of a series of horrifically graphic acts of vengeance.

The remaining gang members try to neutralize their unknown adversary.

Eventually, they draw in the characters of Wong’s blind sister and ex-brother-in-law

– the former displaying self-sacrificial heroism, the latter some excellent

kung fu in a wheelchair! The final confrontation involves the martial power

of Billy Chow.

Wong’s character portrays both suffering and resilience.

She attempts to enlist the aid of her former brother-in-law (Lam) – an

ex-triad now confined to a wheelchair. A lounge owner in HK, he hires

her as a waiter and finds her a place to live, but refuses to help in her

quest for vengeance. She, however, has other ideas. When a

chance encounter provides access to the first assailant (Shing), she improvises

the first of a series of horrifically graphic acts of vengeance.

The remaining gang members try to neutralize their unknown adversary.

Eventually, they draw in the characters of Wong’s blind sister and ex-brother-in-law

– the former displaying self-sacrificial heroism, the latter some excellent

kung fu in a wheelchair! The final confrontation involves the martial power

of Billy Chow.

In this film the nature and intensity of the violence

go beyond most titles, as does the depravity of most of the male characters’

acts. When Wong’s character finally staggers away from what she’s

done, it seems like a justifiable cleansing. Throughout it all, Wong’s

expressive countenance registers each nuance of pain, disgust and anger.

In this film the nature and intensity of the violence

go beyond most titles, as does the depravity of most of the male characters’

acts. When Wong’s character finally staggers away from what she’s

done, it seems like a justifiable cleansing. Throughout it all, Wong’s

expressive countenance registers each nuance of pain, disgust and anger.

“In the Line of Duty III” (1988)

(D & B Films Co.; Dirs. Arthur Wong Ngok-tai,

Brandy Yeun Chun-yeung)

Cynthia Khan’s first foray into the police

action genre benefited enormously from the presence of Michiko Nishiwaki

as a Japanese terrorist femme fatale. Nishiwaki simply sizzles, and

almost steals the film. She and her terrorist partner “Nakamura”

(Stuart Ong) perform a spectacularly violent jewelry robbery at a Tokyo

show. Pursued by the partner of a slain detective, the couple flees

to HK, only to discover that the jewels are fake. They then target

the double-crossing designer and the pursuing detective, before finally

turning on the HK police themselves.

Cynthia Khan performs very well as “Madam Yeung,”

the HK police officer assigned to the case, especially during her early

scenes while arresting a street criminal and raiding an illegal weapons

factory. Her later martial arts duels with Dick Wei (as one of the

Japanese terrorists) seem less convincing. Nevertheless, the chases,

shootouts and combats along the way are well filmed and energetically performed.

Only the final fight disappoints, lacking the precision and energy in the

finale of the two preceding titles in the series. Despite this, Yeung

and Nishiwaki develop a visceral animosity that turbocharges the plot.

Neither will leave the other alone, and each pursues the other with a fanaticism

bordering on the irrational. This collision between the seductive

Nishiwaki and straight-laced Yeung may be the most provocatively sensual

element of the entire “In the Line of Duty” series.

Cynthia Khan performs very well as “Madam Yeung,”

the HK police officer assigned to the case, especially during her early

scenes while arresting a street criminal and raiding an illegal weapons

factory. Her later martial arts duels with Dick Wei (as one of the

Japanese terrorists) seem less convincing. Nevertheless, the chases,

shootouts and combats along the way are well filmed and energetically performed.

Only the final fight disappoints, lacking the precision and energy in the

finale of the two preceding titles in the series. Despite this, Yeung

and Nishiwaki develop a visceral animosity that turbocharges the plot.

Neither will leave the other alone, and each pursues the other with a fanaticism

bordering on the irrational. This collision between the seductive

Nishiwaki and straight-laced Yeung may be the most provocatively sensual

element of the entire “In the Line of Duty” series.

Two very brief cameos worth watching for are Sandra

Ng as a police officer and Robin Shou as a bodyguard who leaves the duplicitous

fashion designer to the none-too-tender mercies of Nishiwaki’s and Yung’s

terrorist duo.

Two very brief cameos worth watching for are Sandra

Ng as a police officer and Robin Shou as a bodyguard who leaves the duplicitous

fashion designer to the none-too-tender mercies of Nishiwaki’s and Yung’s

terrorist duo.

“On the Run” (1988)

(Golden Harvest/Bo Ho Films Co./Mobile Film

Production/Paragon Films; Dir. Alfred Cheung Kin-ting)

This film’s numerous action episodes really

only serve as a context for the superior acting of Pat Ha and Yuen Biao

as their characters’ screen relationship unfolds. When his police

detective ex-wife is shot dead in a restaurant, “Hsiang Ming” (Yuen Biao)

is initially frustrated by the negative impact on his emigration prospects!

After quickly apprehending and overpowering the killer, “Miss Pai” (Pat

Ha), things become even more complicated for Hsiang as he realizes that

she and he are now targets of his erstwhile colleagues – corrupt detectives

seeking to cover evidence of their own drug crimes. Framed for murder,

Hsiang’s options rapidly contract as the killers target his elderly mother

and young daughter. Wounded, Hsiang is forced to rely on the assassin

Pai, who slowly discovers warmth while caring for him and his young daughter.

There is not a shred of false sentiment in this

rather harrowing tale that depicts HK as a claustrophobic place in which

it is hard to truly hide or shake off pursuit. Sparing dialog, deep

shadows and a rather grim exploration of pursuit and paranoia evoke film

noir. Pat Ha is excellent as a quirky contract assassin from Thailand

who superficially seems a 60s throwback in her miniskirt and permed hair.

But she takes no prisoners, drilling numerous bad guys with her semiautomatic

pistol with dispassionate precision. Such coldness contrasts with

her character’s spontaneity and warmth with Hsiang’s little daughter.

There is not a shred of false sentiment in this

rather harrowing tale that depicts HK as a claustrophobic place in which

it is hard to truly hide or shake off pursuit. Sparing dialog, deep

shadows and a rather grim exploration of pursuit and paranoia evoke film

noir. Pat Ha is excellent as a quirky contract assassin from Thailand

who superficially seems a 60s throwback in her miniskirt and permed hair.

But she takes no prisoners, drilling numerous bad guys with her semiautomatic

pistol with dispassionate precision. Such coldness contrasts with

her character’s spontaneity and warmth with Hsiang’s little daughter.

The absurdity of such intimacy between a child

and her mother’s killer is rammed home when Pai prompts the girl to play

a rhyming game of head motions. As the girl moves her head just enough,

Pai shoots the man holding her through his head.

The absurdity of such intimacy between a child

and her mother’s killer is rammed home when Pai prompts the girl to play

a rhyming game of head motions. As the girl moves her head just enough,

Pai shoots the man holding her through his head.

After exhausting their resources, Hsiang and Pai

confront the police detectives who have orchestrated the entire affair.

This climax is one of the more protracted and uncomfortable to watch in

the entire genre. Vengeance, in this film, is total.

After exhausting their resources, Hsiang and Pai

confront the police detectives who have orchestrated the entire affair.

This climax is one of the more protracted and uncomfortable to watch in

the entire genre. Vengeance, in this film, is total.